|

| |

|

© Eric R. Pianka Sexual Selection and Mating Systems Given that an organism is to mix its genes with those of another individual (i.e., it is to reproduce sexually), just which other individual those genes are mixed with can make a substantial difference. By virtue of associating its genes with "good" genes, an organism mating with a very fit partner passes its own genes on to future generations more effectively than another genetically identical individual (twin) mating with a less fit partner. Thus, those members of any population that make the best matings leave a statistically greater contribution to future generations. As a result, within each sex there is competition for the best mates of the opposite sex; this leads to the intrasexual component of sexual selection. Intrasexual selection usually generates antagonistic and aggressive interactions between members of a sex, with those individuals best able to dominate other individuals of their own sex being at a relative advantage. Often, direct physical battle is unnecessary and mere gestures (and/or various other signals of "strength") are enough to determine which individual "wins" an encounter. This makes some selective sense, for if the outcome of a fight is relatively certain, little if anything can be gained from actually fighting; in fact, there is some disadvantage due to the finite risk of injury to both contestants. Similar considerations apply in the defense of territories.  Maynard Smith (1956) convincingly demonstrated mating preferences in laboratory

populations of the fruit fly Drosophila subobscura. Females of these little flies

usually mate only once during their lifetime and store sperm in a seminal receptacle.

Males breed repeatedly. Genetically similar females were mated to two different

strains of males, one inbred (homozygous) and the other outbred (heterozygous), and

all eggs laid by these females during their entire lifetimes were collected. A similar

total number of eggs were laid by both groups of females, but the

percentage of eggs that hatched differed markedly. Females mated to inbred males

laid an average of only 264 fertile eggs each, whereas those bred to outbred males

produced an average of 1134 fertile eggs per female (and hence produced over four

times as many viable offspring). Maynard Smith reasoned that there should therefore

be strong selection for females to mate with outbred rather than with inbred

males. When virgin females were placed in a bottle with outbred males, mating

occurred within an hour in 90 percent of the cases; however, when similar virgins

were offered inbred males, only 50 percent mated during the first hour. Both kinds

of males courted females vigorously and repeatedly attempted to mount females,

but outbred males were much more successful than inbred ones. By carefully

watching their elaborate courtship behavior, Maynard Smith discovered that inbred

males responded more slowly than outbred males to the rapid side-step dance of

females. Presumably as a result of this lagging, females often rejected advances of

inbred males and flew away before being inseminated. These observations clearly

show that females exert a preference as to which males they will accept. Similar

mating preferences almost certainly exist in most natural populations, although they

are usually difficult to demonstrate.

Maynard Smith (1956) convincingly demonstrated mating preferences in laboratory

populations of the fruit fly Drosophila subobscura. Females of these little flies

usually mate only once during their lifetime and store sperm in a seminal receptacle.

Males breed repeatedly. Genetically similar females were mated to two different

strains of males, one inbred (homozygous) and the other outbred (heterozygous), and

all eggs laid by these females during their entire lifetimes were collected. A similar

total number of eggs were laid by both groups of females, but the

percentage of eggs that hatched differed markedly. Females mated to inbred males

laid an average of only 264 fertile eggs each, whereas those bred to outbred males

produced an average of 1134 fertile eggs per female (and hence produced over four

times as many viable offspring). Maynard Smith reasoned that there should therefore

be strong selection for females to mate with outbred rather than with inbred

males. When virgin females were placed in a bottle with outbred males, mating

occurred within an hour in 90 percent of the cases; however, when similar virgins

were offered inbred males, only 50 percent mated during the first hour. Both kinds

of males courted females vigorously and repeatedly attempted to mount females,

but outbred males were much more successful than inbred ones. By carefully

watching their elaborate courtship behavior, Maynard Smith discovered that inbred

males responded more slowly than outbred males to the rapid side-step dance of

females. Presumably as a result of this lagging, females often rejected advances of

inbred males and flew away before being inseminated. These observations clearly

show that females exert a preference as to which males they will accept. Similar

mating preferences almost certainly exist in most natural populations, although they

are usually difficult to demonstrate.

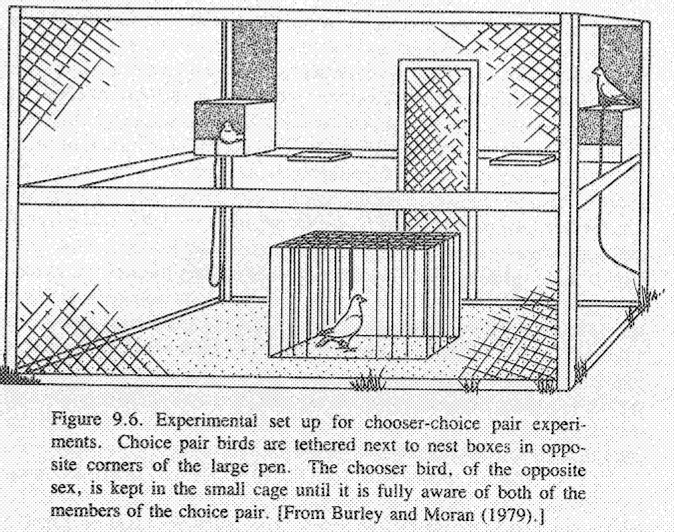

In an elegant study of mate choice among captive feral pigeons, Burley and Moran

(1979) and Burley (1981b) demonstrated clear mating preferences among these

monogamous birds. Pair bonds were first broken and pigeons kept isolated by sex

for several months. Then a "chooser" bird was offered a "choice pair" of potential

mates of the opposite sex. Pigeons in such a choice pair were tethered to prevent

direct physical contact and differed from one another in a given phenotypic aspect

such as age, plumage color, or past reproductive experience. Choosers selected

mates with reproductive experience over inexperienced birds and tended to reject

very old potential mates in favor of younger ones. A clear hierarchy in preference

for plumage traits was also evident; "blue" birds were almost invariably preferred

over "ash red" birds, and among female choosers, "blue check" males were chosen

over "blue bar" males (either blue phenotype was in turn preferred over "ash red").

Over evolutionary time, natural selection operates to produce a correlation between

male genetic quality and female preference because those females preferring males of

superior genetic quality would associate their own genes with the best

males' genes and therefore produce high-quality sons (female quality is correlated

with male preference for the same reason). This can be termed the "good genes" or

"sexy son" phenomenon. Female preference also enhances male fitness directly,

making it difficult to separate female choice from male fitness. Certain female fish

appear to copy mating choices of other females (Dugatkin 1996; Schlupp et al.

1994).

In an elegant study of mate choice among captive feral pigeons, Burley and Moran

(1979) and Burley (1981b) demonstrated clear mating preferences among these

monogamous birds. Pair bonds were first broken and pigeons kept isolated by sex

for several months. Then a "chooser" bird was offered a "choice pair" of potential

mates of the opposite sex. Pigeons in such a choice pair were tethered to prevent

direct physical contact and differed from one another in a given phenotypic aspect

such as age, plumage color, or past reproductive experience. Choosers selected

mates with reproductive experience over inexperienced birds and tended to reject

very old potential mates in favor of younger ones. A clear hierarchy in preference

for plumage traits was also evident; "blue" birds were almost invariably preferred

over "ash red" birds, and among female choosers, "blue check" males were chosen

over "blue bar" males (either blue phenotype was in turn preferred over "ash red").

Over evolutionary time, natural selection operates to produce a correlation between

male genetic quality and female preference because those females preferring males of

superior genetic quality would associate their own genes with the best

males' genes and therefore produce high-quality sons (female quality is correlated

with male preference for the same reason). This can be termed the "good genes" or

"sexy son" phenomenon. Female preference also enhances male fitness directly,

making it difficult to separate female choice from male fitness. Certain female fish

appear to copy mating choices of other females (Dugatkin 1996; Schlupp et al.

1994).

As a result of such mating preferences, populations have breeding structures. At one extreme is inbreeding, in which genetically similar organisms mate with one another (homogamy); at the other extreme is outbreeding, in which unlikes mate with each other (heterogamy). Outbreeding leads to association of unlike genes and thus generates genetic variation. Inbreeding produces genetic uniformity at a local level, although variability may persist over a broader geographic region. Both extremes represent nonrandom breeding structures; randomly mating panmictic populations described by the Hardy-Weinberg equation of population genetics lie midway between them. However, probably no natural population is truly panmictic. Animal populations also have mating systems. Most insectivorous birds and carnivorous birds and mammals are monogamous (although extra-pair copulations do occur), with a pair bond between one male and one female. In such a case, both parents typically care for the young. Polygamy refers to mating systems in which one individual maintains simultaneous or sequential pair bonds with more than one member of the opposite sex. There are two kinds of polygamy, depending on which sex maintains multiple pair bonds. In some birds, such as marsh wrens and yellow-headed blackbirds, one male may have pair bonds with two or more females at the same time (polygyny). Much less common is polyandry, in which one female has simultaneous pair bonds with more than one male; polyandry occurs in a few bird species, such as some jacanas, rails, and tinamous. In some species, a male has several short pair bonds with different females in sequence; typically, each such pair bond lasts only long enough for completion of copulation and insemination. This occurs in a variety of birds (including some grackles, hummingbirds, and grouse) and mammals (many pinnepeds and some ungulates). Finally, an idealized mating system (perhaps, more appropriately, a lack of a mating system) is promiscuity, in which each organism has an equal probability of mating with every other organism. True promiscuity is extremely unlikely and probably nonexistent; it would result in a panmictic population. It may be approached in some invertebrates such as certain polychaete worms and crinoid echinoderms, which shed their gametes into the sea, or in terrestrial plants that release pollen to the wind, where they are mixed by currents of water and air. However, various forms of chemical discrimination of gametes -- and therefore mating preferences -- probably occur even in such sessile organisms.  The intersexual component of sexual selection (that occurring between the sexes) is

termed epigamic selection (Darwin 1871). It is often defined as "the reproductive

advantage accruing to those genotypes that provide the stronger heterosexual stimuli,"

but it is also aptly described as "the battle of the sexes." Epigamic selection

operates by mating preferences. Of prime importance is the fact that what maximizes

an individual male's fitness is not necessarily coincident with what is best for

an individual female, and vice versa. As an example, in most vertebrates, individual

males can usually leave more genes under a polygynous mating system, whereas an

individual female is more likely to maximize her reproductive success under a

monogamous or polyandrous system. Sperm are small, energetically inexpensive to

produce, and are produced in large numbers. As a result, vertebrate males have

relatively little invested in each act of reproduction and can and do mate frequently

and rather indiscriminately (i.e., males tend toward promiscuity). Vertebrate

females, on the other hand, often or usually have much more invested in each act of

reproduction because eggs and/or offspring are usually energetically expensive.

Because females have so much more at stake in each act of reproduction, they tend

to exert much stronger mating preferences than males and to be more selective as

to acceptable mates (the sex that invests most is the choosier, thereby exerting

strong pressure on evolution of the opposite sex). Female choice can be an

exceedingly powerful force in male evolution, sometimes generating extreme sexual

dimorphisms. By refusing to breed with promiscuous and

polygnous males, vertebrate females can sometimes "force" males to become

monogamous and to contribute their fair share toward raising the offspring. In effect,

polygyny is the outcome of the battle of the sexes when the males win out (patriarchy),

whereas polyandry is the outcome when females win out (matriarchy). Monogamy is a

compromise between these two extremes.

The intersexual component of sexual selection (that occurring between the sexes) is

termed epigamic selection (Darwin 1871). It is often defined as "the reproductive

advantage accruing to those genotypes that provide the stronger heterosexual stimuli,"

but it is also aptly described as "the battle of the sexes." Epigamic selection

operates by mating preferences. Of prime importance is the fact that what maximizes

an individual male's fitness is not necessarily coincident with what is best for

an individual female, and vice versa. As an example, in most vertebrates, individual

males can usually leave more genes under a polygynous mating system, whereas an

individual female is more likely to maximize her reproductive success under a

monogamous or polyandrous system. Sperm are small, energetically inexpensive to

produce, and are produced in large numbers. As a result, vertebrate males have

relatively little invested in each act of reproduction and can and do mate frequently

and rather indiscriminately (i.e., males tend toward promiscuity). Vertebrate

females, on the other hand, often or usually have much more invested in each act of

reproduction because eggs and/or offspring are usually energetically expensive.

Because females have so much more at stake in each act of reproduction, they tend

to exert much stronger mating preferences than males and to be more selective as

to acceptable mates (the sex that invests most is the choosier, thereby exerting

strong pressure on evolution of the opposite sex). Female choice can be an

exceedingly powerful force in male evolution, sometimes generating extreme sexual

dimorphisms. By refusing to breed with promiscuous and

polygnous males, vertebrate females can sometimes "force" males to become

monogamous and to contribute their fair share toward raising the offspring. In effect,

polygyny is the outcome of the battle of the sexes when the males win out (patriarchy),

whereas polyandry is the outcome when females win out (matriarchy). Monogamy is a

compromise between these two extremes.

Under a monogamous mating system, a male must be certain that the offspring are his own; otherwise, he might expend energy raising offspring of another male (note that females do not have this problem). No wonder monogamous males jealously guard their females against stolen copulations! Nevertheless, cuckoldry is not infrequent (females can sometimes gain a fitness advantage by cheating on their mates -- see discussion of alternative mating tactics below). Certainty of paternity is a serious problem for males, but females can be confident that their progeny are indeed their own (female parentage is certain). On the other hand, females mated monogamously are vulnerable to desertion once reproduction is underway.  Let us now examine ecological determinants of mating systems. Some assert that

sex ratios "drive" mating systems; under such an interpretation, polygyny arises

when males are in short supply and polyandry occurs when there are not enough

females to go around. According to this explanation, many species are monogamous

simply because sex ratios are often near equality. In fact, quite the reverse is

true, with sexual selection and mating systems indirectly and directly determining

sexual dimorphisms and hence various sex ratios (Willson and Pianka 1963). In many

birds and some mammals, floating populations of nonbreeding males exist. These can

be demonstrated by simply removing breeding individuals; typically, they are quickly

replaced with younger and less experienced animals (Stewart and Aldrich 1951; Hensley and

Cope 1951; Orians 1969).

Let us now examine ecological determinants of mating systems. Some assert that

sex ratios "drive" mating systems; under such an interpretation, polygyny arises

when males are in short supply and polyandry occurs when there are not enough

females to go around. According to this explanation, many species are monogamous

simply because sex ratios are often near equality. In fact, quite the reverse is

true, with sexual selection and mating systems indirectly and directly determining

sexual dimorphisms and hence various sex ratios (Willson and Pianka 1963). In many

birds and some mammals, floating populations of nonbreeding males exist. These can

be demonstrated by simply removing breeding individuals; typically, they are quickly

replaced with younger and less experienced animals (Stewart and Aldrich 1951; Hensley and

Cope 1951; Orians 1969).

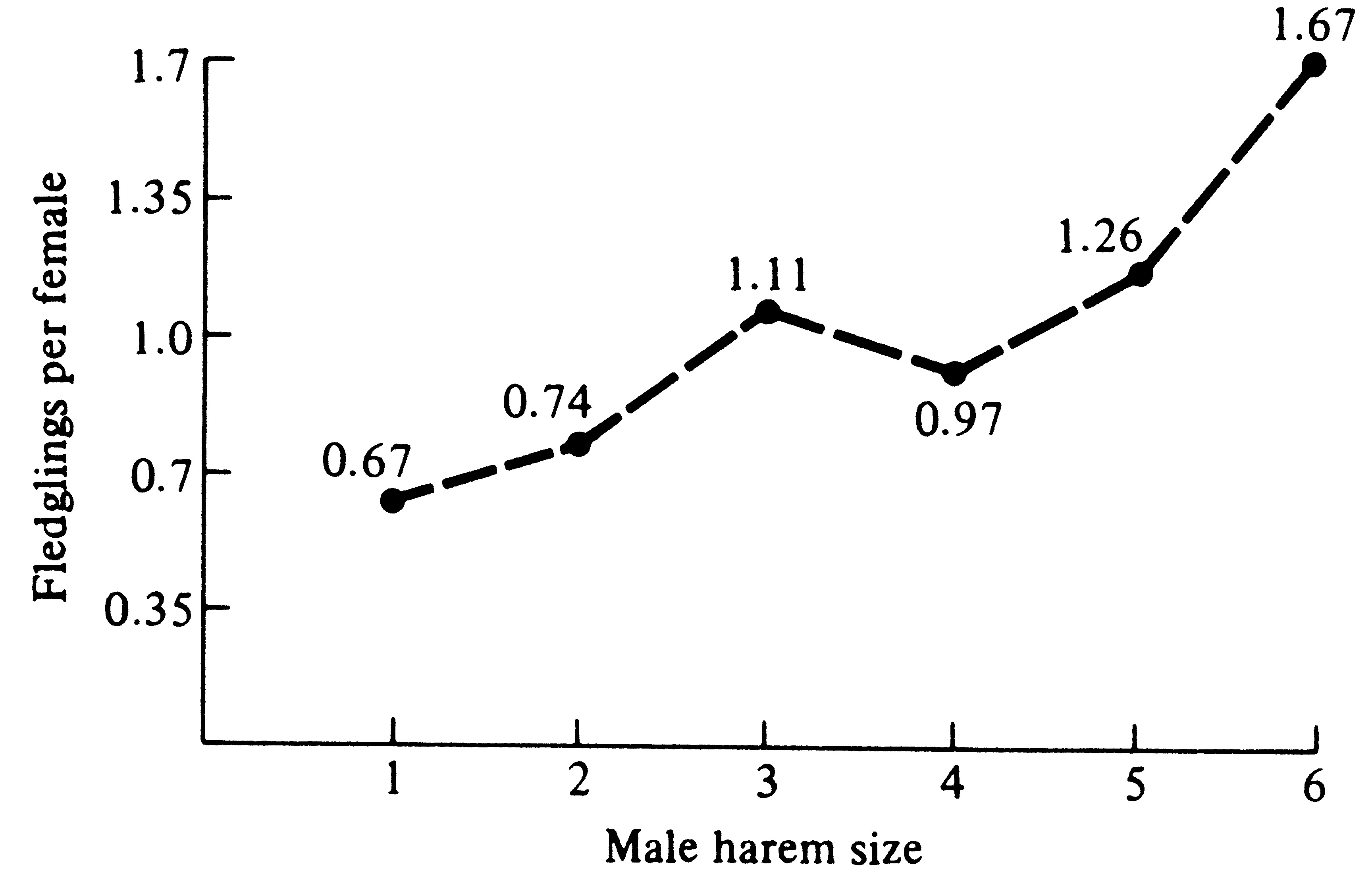

Only 14 of the 291 species (5 percent) of North American passerine birds are regularly polygynous (Verner and Willson 1966). Some 11 of these 14 (nearly 80 percent) breed in prairies, marshes, and savanna habitats. Verner and Willson suggested that in these extremely productive habitats, insects are continually emerging and thus food supply is rapidly renewed; as a result, several females can successfully exploit the same feeding territory. However, a similar review of the nesting habitats used by polygynous passerines in Europe (which also constitute about 5 percent of the total number of species) showed no such prevalence toward grassland or marshy habitats (Haartman 1969). Indeed, for elusive reasons, Haartman suggested that closed-in, safe nests were a more important determinant of polygynous mating systems than were breeding habitats. Crook (1962, 1963, 1964, 1965) has suggested that among African weaverbirds, monogamy is evolved when food is scarce and both parents are necessary to raise the young, whereas polygyny evolves in productive habitats with abundant food where male assistance is less essential. This argument, of course, ignores entirely "the battle of the sexes" (epigamic selection).  Polygyny in long-billed marsh wrens was studied in the field in Washington State

(Verner 1964). Male wrens build dummy nests (not used by females) scattered

around their territories; during courtship, females are escorted around a male's

entire territory and shown each dummy nest (this presumably allows females to

assess the quality of a male's territory). Some males possessed two females (one

male had three), whereas males on adjacent territories had only one female or none

at all. Territories of bigamous and trigamous males were not only larger than those

of bachelors and monogamous males, but they also contained more emergent vegetation

(where female wrens forage). Verner reasoned that a female must be able to

raise more young by pairing with a mated male on a superior territory than by

pairing with a bachelor on an inferior territory even though she obtains less help from

her mate. This has since been demonstrated in red-winged blackbirds (Figure 10.6).

Verner noted that evolution of polygyny depends on males being able to defend

territories containing enough food to support more than one female and her offspring;

this condition for evolution of polygyny requires fairly productive habitats.

Polygyny in long-billed marsh wrens was studied in the field in Washington State

(Verner 1964). Male wrens build dummy nests (not used by females) scattered

around their territories; during courtship, females are escorted around a male's

entire territory and shown each dummy nest (this presumably allows females to

assess the quality of a male's territory). Some males possessed two females (one

male had three), whereas males on adjacent territories had only one female or none

at all. Territories of bigamous and trigamous males were not only larger than those

of bachelors and monogamous males, but they also contained more emergent vegetation

(where female wrens forage). Verner reasoned that a female must be able to

raise more young by pairing with a mated male on a superior territory than by

pairing with a bachelor on an inferior territory even though she obtains less help from

her mate. This has since been demonstrated in red-winged blackbirds (Figure 10.6).

Verner noted that evolution of polygyny depends on males being able to defend

territories containing enough food to support more than one female and her offspring;

this condition for evolution of polygyny requires fairly productive habitats.

|

|

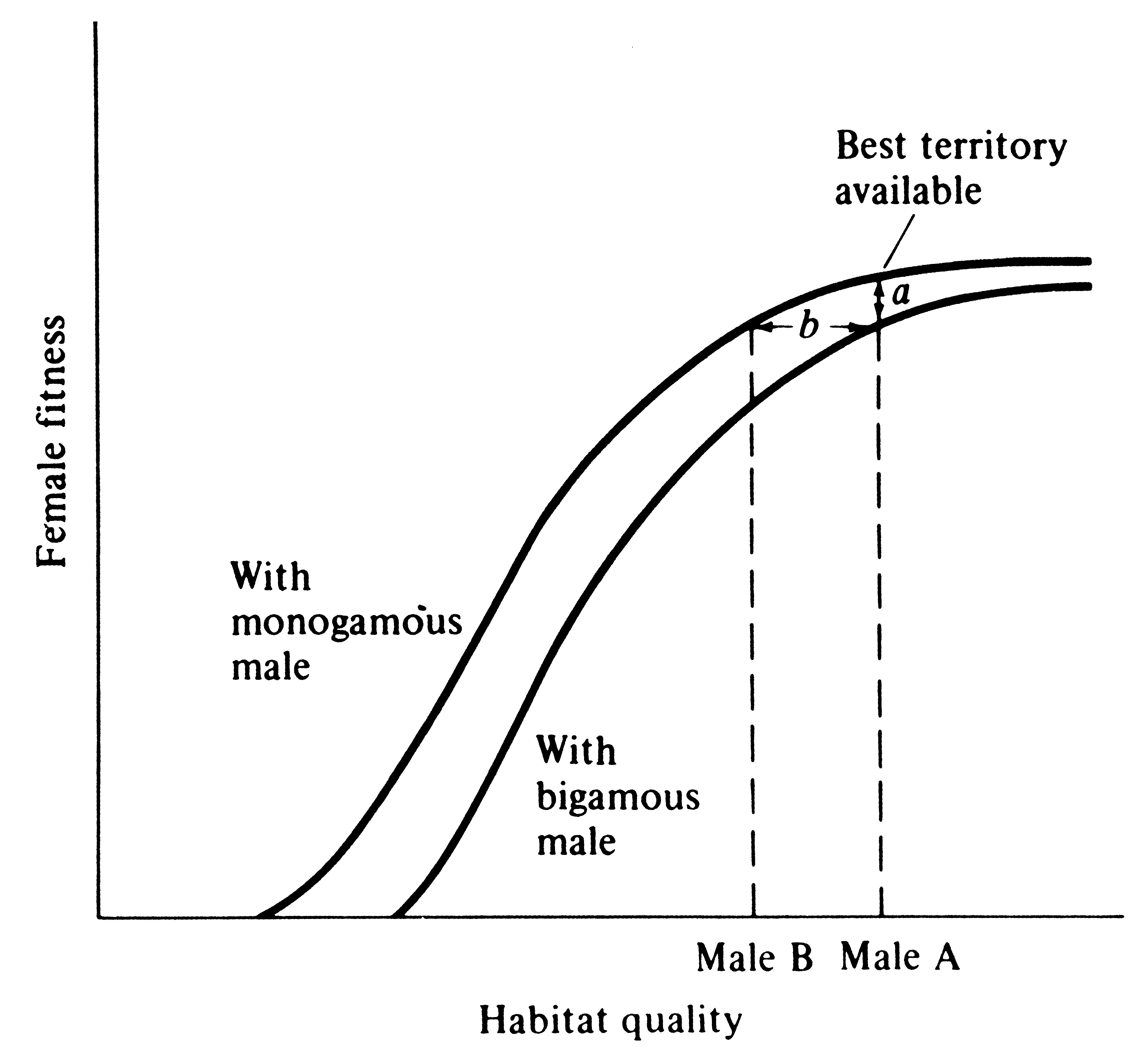

Female wrens are antagonistic toward each other, and as a result, males cannot make a second mating until their first female is incubating; a temporal staggering of females is produced (Verner 1965). Building on Verner's work and studies on blackbirds, Verner and Willson (1966) defined the polygyny threshold as the minimum difference in habitat quality of territories held by males in the same general region that is sufficient to favor bigamous matings by females (Figure 10.7). Polygyny is much more prevalent in mammals than in birds, presumably because in most mammals females nurse their young and, at least among herbivorous species, males can do relatively little * to assist females in raising the young (such species typically have a pronounced sexual dimorphism). A notable exception is carnivorous mammals that are often monogamous during the breeding season, with males participating in feeding both female and young (typically sexual dimorphisms are slight in such species). Similarly, most carnivorous and insectivorous birds are monogamous, and males can and do gather food for nestlings. Often, sexual dimorphism in such bird species is slight, and those that are dimorphic are usually migratory (sexual dimorphism may promote rapid pairing as well as species recognition). Birds whose young are well developed at hatching (precocial as opposed to altricial birds) typically have little male parental care and are frequently polygynous, with pronounced sexual dimorphisms. * Why male mammals do not lactate remains an unresolved evolutionary question (Daly 1979).

|

|

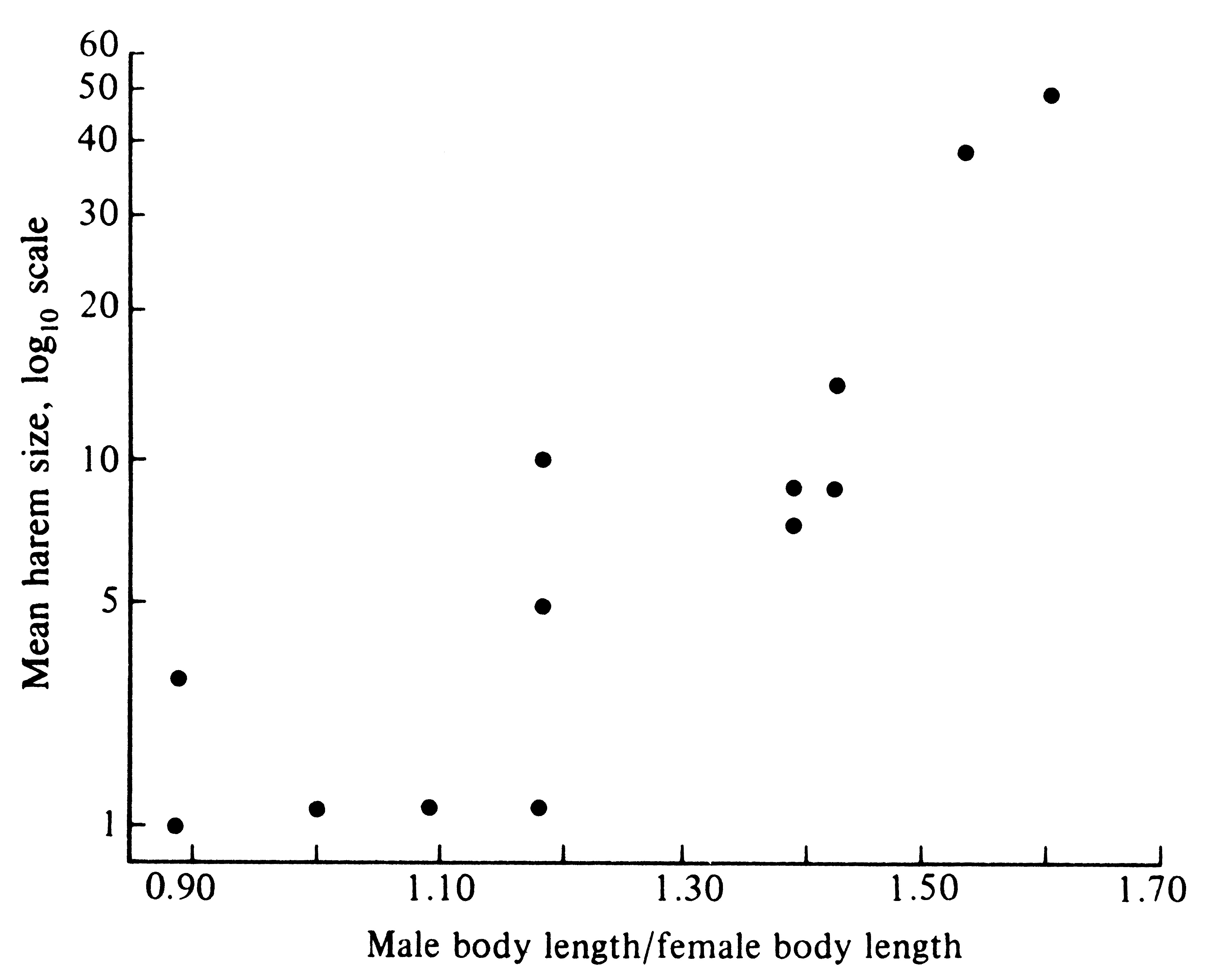

Given a population sex ratio near equality and a monogamous mating system, every individual (both male and female) has a substantial opportunity to breed and to pass on its genes; however, with an equal population sex ratio and polygyny, a select group of the fittest males makes a disproportionate number of matings. Dominant battle-scarred males of the northern sea lion, Eumetopias jubata, that have "won" rocky islets where most copulations occur, often have harems of 10 to 20 females. Under such circumstances, these males sire most progeny and their genes constitute half the gene pool of the subsequent generation. Because those heritable characteristics making them good fighters and dominant animals are passed on to their sons, contests over the breeding grounds may be intensified in the next generation. Only winning males are able to perpetuate their genes. As a result of this intense competition between males for the breeding grounds, intrasexual selection has favored a striking sexual dimorphism in size. Whereas adult females usually weigh less than 500 kilograms, adult males may weigh as much as 1000 kilograms. Sexual dimorphism in size is even more pronounced in the California sea lion, Zalophus californianus, where females attain weights of only about 100 kilograms, whereas males reach nearly 500 kilograms. Among 13 species of these pinniped mammals, sexual size dimorphisms are more pronounced in species that have larger harems (Figure 10.8). Presumably, the upper limit on such a differential size escalation is set by various other ecological determinants of body size, such as predation pressures, foraging efficiency, and food availability.

|

|

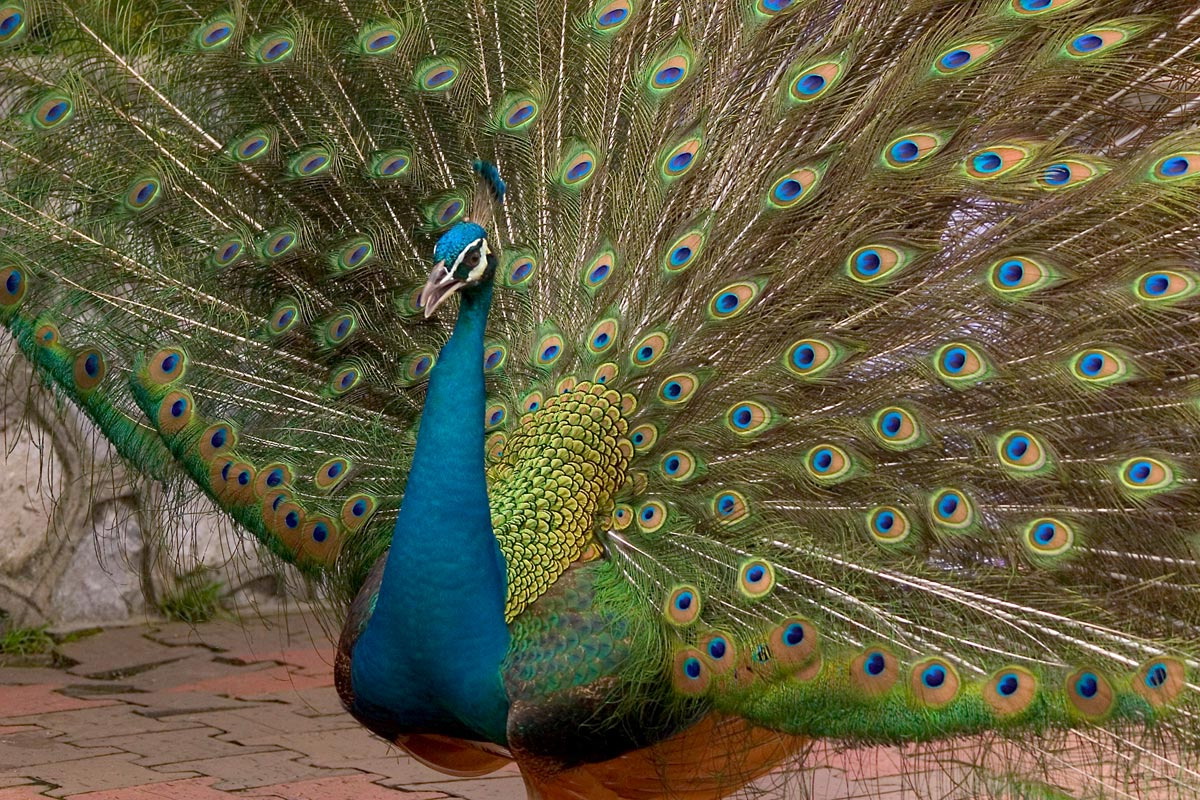

Somewhat analogous situations occur among various polygynous birds. Many species of grouse exhibit multiple short pair bonds, lasting only long enough for copulation, with males displaying their sexual prowess in groups termed "leks." Dominant, usually older, males occupy the central portion of the communal breeding grounds and make a disproportionate percentage of matings. Receptive females rush past peripheral males to get to central males for copulation. Strong sexual dimorphisms in size, plumage, color, and behavior exist in many grouse. In addition to intrasexual selection, epigamic selection operating through female choice can also produce and maintain sexual dimorphisms; usually both types of sexual selection occur simultaneously, and it is often difficult to disentangle their effects. Indeed, by choosing to mate with gaudy and conspicuous males, females have presumably forced the evolution of some bizarre male sexual adaptations, such as peacock tails or the long tails of some male birds of paradise (this is known as runaway sexual selection). Certain bower birds have avoided becoming overly gaudy (and hence dangerously conspicuous) by evolving a unique behavioral adaptation; males build highly ornamented bowers that are used to attract and to court females and that signal the male's intersexual attractiveness. Interestingly, male bower birds also demolish and steal from other male's bowers. Frequently, if not usually, the same sexual characteristics (such as size, color, plumage, song, behavior) advertise both intrasexual prowess and intersexual attractiveness. This makes evolutionary sense because an individual's overall fitness is determined by its success at coping with both types of sexual selection, which should usually be positively correlated; moreover, economy of energy expenditure is also obtained by consolidation of sexual signals.  Extravagant male traits such as a peacock's tail could be exploited by females as

indicators of the male's ability to survive despite his handicap (Zahavi 1975, 1977;

Evans 1991). This "handicap hypothesis" was extended by Hamilton and Zuk

(1982), who suggest that females might also assess a male's resistance to parasites

by the brightness or elaborateness of his epigamic colors or display.

In some cases, males seem to have evolved to exploit pre-existing sensory biases of

females (Andersson 1994). For example, some male insects exploit fragrances of

fruit foods as pheromones that attract females. Likewise, calls of male tungara frogs

appear to have evolved in response to sensory biases of female frogs (Ryan 1990;

Ryan and Keddy-Hector 1992; Ryan and Rand 1990; Ryan et al. 1990).

Such "sensory exploitation" suggests that female mating preferences can evolve

without sexual selection and in ways that do not necessarily enhance female fitness.

Viewed in this way, males evolutionarily exploit the built-in sensory drive of

females, thus increasing their own fitness but not necessarily that of females. Such

female "choice" without a fitness advantage for females would seem unlikely to

endure if natural selection could operate on variation in female "preference."

Extravagant male traits such as a peacock's tail could be exploited by females as

indicators of the male's ability to survive despite his handicap (Zahavi 1975, 1977;

Evans 1991). This "handicap hypothesis" was extended by Hamilton and Zuk

(1982), who suggest that females might also assess a male's resistance to parasites

by the brightness or elaborateness of his epigamic colors or display.

In some cases, males seem to have evolved to exploit pre-existing sensory biases of

females (Andersson 1994). For example, some male insects exploit fragrances of

fruit foods as pheromones that attract females. Likewise, calls of male tungara frogs

appear to have evolved in response to sensory biases of female frogs (Ryan 1990;

Ryan and Keddy-Hector 1992; Ryan and Rand 1990; Ryan et al. 1990).

Such "sensory exploitation" suggests that female mating preferences can evolve

without sexual selection and in ways that do not necessarily enhance female fitness.

Viewed in this way, males evolutionarily exploit the built-in sensory drive of

females, thus increasing their own fitness but not necessarily that of females. Such

female "choice" without a fitness advantage for females would seem unlikely to

endure if natural selection could operate on variation in female "preference."

Alternative mating tactics exist for both females and males. Males often can increase their reproductive success by extra-pair copulations. A female mated to an average or substandard male can increase the fitness of her progeny by becoming impregnated with the sperm of a superior male (such "stolen copulations" allow the female to produce more attractive sons than she would otherwise, but because her male mate has been cuckolded, his fitness is greatly reduced -- this has led to the evolution of jealousy among males). Still another interesting alternative mating tactic is satellite males. In crickets and frogs, males call to attract mates and females are attracted to superior males by characteristics of their calls. But calling can be hazardous because it also attracts parasites and predators. So-called "satellite" males do not call, but station themselves around calling males and intercept females coming in to mate. Still another male alternative mating tactic is so called "sneaker" males that mimic females so as not to arouse aggression of normal males -- such sneakers obtain copulations when the real males aren't watching. Sexual dimorphisms sometimes serve still another ecological function, by reducing niche overlap and competition between the sexes. In certain island lizards (Schoener 1967, 1968a) and some birds (Selander 1966), strong sexual dimorphisms in the feeding apparatus (jaws and beaks, respectively) are correlated with differential utilization of food resources. Burley, N. 1977. Parental investment, mate choice, and mate quality. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74: 3476-3479. Burley, N. and N. Moran. 1979. The significance of age and reproductive experience in mate preferences of feral pigeons, Columba livia. Anim. Behavior 27: 686-695. Darwin, C. 1871. Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man. John Murray, London. Fisher, R. A. 1930. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Hamilton, W. D. and M. Zuk. 1982. Heritable true fitness and bright birds: a role for parasites? Science 218: 384-387. Maynard Smith, J. 1956. Fertility, mating behavior, and sexual selection in Drosophila subobscura. J. Genet. 54: 261-279. Orians, G. H. 1969. On the evolution of mating systems in birds and mammals. Amer. Natur. 103: 589-603. Pianka, E. R. 2000. Evolutionary Ecology, 6th ed. Addison-Wesley-Longman, San Francisco. Verner, J. 1964. Evolution of polygamy in the long-billed marsh wren. Evolution 18: 252-261. Verner, J. and M. F. Willson. 1966. The influence of habitats on mating systems of North American passerine birds. Ecology 47: 143-147. Willson, M. F. and E. R. Pianka. 1963. Sexual selection, sex ratio, and mating system. American Naturalist 97: 405-407. Zahavi, A. 1975. Mate selection -- a selection for a handicap. J. Theor. Biol. 53: 205-214. Zahavi, A. 1977. The cost of honesty (further remarks on the handicap principle). J. Theor. Biol. 67: 603-605. Zuk, M. 1991. Sexual ornaments as animal signals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 6: 228-231. See also Casper Hewett's Theory of Sexual Selection |