|

Note: This html file should be viewed with Safari

(other browsers do not display it properly)

The Vanishing Book of Life on Earth

© Eric R. Pianka

Russian translation by Sandi Wolfe

The great North American tall grass prairie -- we just took it and turned it

all into agricultural lands. We exterminated the bison, wiped out the

Indians, destroyed the prairie dogs and those black-faced ferrets. We just

erased an entire ecosystem. Now this was very nice for Americans because that

rich topsoil has allowed us to grow lots of food to feed ourselves and the

rest of the world and we've grown fat and apathetic and miserable as a result

of it. We've lost the bison -- we've lost an awful lot that we'll never be

able to recover.

This essay is about an impending doomsday. I am going to take you down, down, down and

then I'll try to rise up with a little bit of optimism at the end.

The great early American naturalist Henry David Thoreau embraced wilderness and used a

book as a metaphor for life on Earth. Philosopher of science Holmes Rolston III extended

Thoreau's metaphor as the "vanishing book of life." Rolston (1985) remarks "destroying

species is like tearing pages out of an unread book, written in a language humans hardly

know how to read." This book of life is disappearing before our eyes. Each page corresponds

to one of the many species of life forms that lived or still lives on Earth, and describes

everything one could possibly want to know about its natural history and ecology, its

parasites, prey, and predators, how it is related to its closest ancestors, as well as

much more. Each chapter, in turn, describes how every member of this myriad of millions

of different microbes, fungi, plants, and animals interact within a particular natural

ecosystem. All of Earth's once pristine ecosystems, past and present, are thus described,

metaphorically, in many volumes.

The great early American naturalist Henry David Thoreau embraced wilderness and used a

book as a metaphor for life on Earth. Philosopher of science Holmes Rolston III extended

Thoreau's metaphor as the "vanishing book of life." Rolston (1985) remarks "destroying

species is like tearing pages out of an unread book, written in a language humans hardly

know how to read." This book of life is disappearing before our eyes. Each page corresponds

to one of the many species of life forms that lived or still lives on Earth, and describes

everything one could possibly want to know about its natural history and ecology, its

parasites, prey, and predators, how it is related to its closest ancestors, as well as

much more. Each chapter, in turn, describes how every member of this myriad of millions

of different microbes, fungi, plants, and animals interact within a particular natural

ecosystem. All of Earth's once pristine ecosystems, past and present, are thus described,

metaphorically, in many volumes.

The massive amount of information contained in all life on Earth could never be recorded

in a single book, or even in an encyclopedia, but would require something more akin to many

libraries of Congress. This "Book of Life" is indeed the most valuable of all of our many

books, as it contains the entire history of all life on Earth from its very beginnings

3,500,000,000 years ago. Unfortunately, this greatest book of all time is tattered and torn,

pages are missing, and entire chapters have been ripped out. Humans are heedlessly destroying

habitats, effectively ripping out pages of the "Book of Life" even before biologists have had

a chance to read them. We are burning the greatest book for nothing more than to expand the

human population, which is already precariously high.

Most people consider biology, particularly ecology, to be a luxury that they can do without.

Even many medical schools in the USA no longer require that pre-medical students obtain a

biological major. Basic biology is not a luxury at all, but rather an absolute necessity.

Despite our

anthropocentric

(human-oriented) attitudes, other life forms are not irrelevant to our own existence.

We need them to continue to exist ourselves. As proven products of natural selection that have

adapted to natural environments over millennia, they have a right to exist, too. With human

populations burgeoning and pressures on space and other limited resources intensifying, we

need all the biological knowledge we can possibly get.

We rely on other organisms for food, medicine, shelter, and clothing. Simply put, humans could

not exist without our symbiotic bacteria, let alone without the endosymbiotic photosynthetic

chloroplasts housed by all green plants. Many of the genes that drive our physiology and metabolic

processes were invented billions of years ago by microbes in Earth's primeval oceans. Even our

blood plasma reflects our ancient origin: it is very close to sea water. We are but one small

branch on the tree of life. We share most of our genes with other organisms, including bacteria

and fungi.

Ecological understanding is particularly vital. Without understanding natural ecosystems, how

can we hope to manage man-made ones wisely? Basic ecological research is extremely urgent simply

because the worldwide press of humanity is rapidly driving other species extinct and destroying

the very systems that ecologists seek to understand. No natural community remains pristine.

Pathetically, many will disappear without even being adequately described, let alone remotely

understood. As existing species go extinct and even entire ecosystems disappear, we lose forever

the very opportunity to study them. Knowledge of their evolutionary history and adaptations

vanishes with them: we are thus losing access to valuable biological information itself. Just as

ecologists in many parts of the world are finally beginning to learn to read the "unread" (and

rapidly disappearing) "book", they are encountering governmental and public hostility and having

a difficult time finding support.

Let us consider the book of life: Several questions come to mind -- Can we read it? Will we be

allowed to try to read it? Do we have time enough left to read it? I have been very fortunate to

have spent most of my life studying the ecology of desert lizards. I'm finding that I am no longer

allowed to do things that I used to be able to do because as we have taken over habitats and

imperiled other species, they have become so scarce that they must be protected. I worry that

before too long ecologists won't be allowed to touch a wild vertebrate. When this happens, time

will have run out for us.

One of the biggest enemies we face is anthropocentrism. This is that common human attitude that

everything on this earth was put here for our use -- to be used any way we want. An example of an

anthropocentric human is a man with a chain saw cutting down a redwood tree that's a thousand

years old. That is audacity and that is anthropocentrism and that is wrong. When you couple

anthropocentrism with technology and human greed, you get a terrible monster, a rapist and

pillager of Earth.

I live in the hills about 35 miles west of Austin, Texas. It's turned into a bedroom community

for the city. All kinds of people move out into the hills to avoid high city taxes in Austin --

they bring their mobile homes, their security lights and their cats and dogs so now there's a

horrible, horrendous commute with new stoplights going in everywhere.

The city of Dripping Springs has had to build three new schools because of this and it's turned

into a little suburb of Austin. Everything has gone downhill. When you meet your new neighbors --

usually over a fence -- they come up and say "Hi, who are you -- what are you doing out here?"

I introduce myself, and they want to know what I do -- how do I make my living? I tell them I'm

a university professor and a lizard ecologist and then I start to plead with them.

I point out that there used to be a lot of lizards and snakes living in these hills and that

they're all disappearing because of this encroaching urbanization. I plead with them not to let

their cats and dogs run loose -- cats are born killers. They let dogs run loose so they can

"play" with the deer. Well, you can't do that -- dogs are wolves -- they pack up and they kill

things. They don't belong out there. Another thing people do is put out feeders for birds --

that brings in urban birds -- blue jays that shouldn't be out there replace the scrub jays that

should be there. I've seen rattlesnakes disappear completely.

When I pleaded with some new neighbors about not letting their cats kill lizards -- one of them

made a huge mistake -- she looked at me and said "what good are lizards?" She shouldn't have

said that to me . . .

I looked her in the eye and said "what good are you?"

Ecologists want and need access to wild organisms in semi-pristine natural environments because

these are the places in which they've evolved and to which they have become adapted. Organisms

don't make any sense if they're not in their natural habitat.

Rattlesnakes . . . People often call me to ask where can they see a rattlesnake. They don't want

to see a wild rattlesnake; they want to see one behind glass. A rattlesnake in cage might as well

be dead as far as I'm concerned. It doesn't have a natural habitat. It doesn't make any sense.

I don't know where it evolved or what it's adapted to; I don't know anything about it.

It's as if you took a a pair of scissors to a collection of the world's greatest love stories and started

cutting out the word "love" every time you saw it and putting the little "loves" into glass vials.

You don't even know which book they came from, let alone whether they are verbs or nouns, you don't

know who loves whom; love has been taken completely out of context. That's what's wrong with animals

in zoos. They don't have any ecologies anymore. They might as well be dead.

We have to save the vanishing book of life, but we must also read it. And my

point as a biologist is that anyone can help save it. There are tree-huggers

galore out there and plenty of people who just want to save the planet.

Anyone can do that. But it takes somebody who's dedicated and earnest and a

little bit crazy to try to go out and read it and try to make sense of it. That's

what we should do if we have the skills and motivation to do it. We should

try to read it before it's gone. I don't see any point in trying to save

anything unless biologists are allowed access to it. I think that is a

critical point here.

Today we have many powerful tools to help us decipher the vanishing book,

most of which were unavailable a few decades ago. These include air travel,

email, fax machines, the global positioning system (GPS), satellite imagery,

geographic information systems (GIS), the polymerase chain reaction (PCR,

which allows amplification of DNA), DNA sequencing, powerful personal desktop

computers and imaginative powerful software. Unfortunately, just as

ecologists have gained access to this vast array of new technological tools,

the very stuff we need to study is disappearing.

Some of these things might not seem very new, but I remember when faxes first

came out -- I was doing field work in Australia and I wanted to send

something to my university in Austin, Texas, and I had access a new fax

machine. As I was feeding it in down under, I could see it in my mind's eye

in now time coming out in Austin -- to me that was mind-boggling technology.

I'm still hoping they'll figure out how to fax me back and forth so that I

can avoid the plane trip.

We've got technology now that is just out of this world. I started using the

Net before it was the Internet, before we had email, it was called the

Arpanet back then -- what I'm finding now with email is that I can have

colleagues anywhere in the world and we can work really fast because if

they're in Australia, when I'm asleep they're working, and when I'm working

they're asleep. We can work 24 hours around the clock, faxing and emailing

stuff back and forth, so our papers just come rolling out.

I wish GPS had been around earlier because when I was out collecting before

lizards were gone from large parts of their geographic ranges I had to record

localities as "15 miles north-northwest of Mojave, California," and

I had to go to a map to try to estimate Latitude and Longitude. It would have

been so much nicer to have a little GPS unit and been able to record these

things accurately; but it's too late now because we've erased big chunks of

information.

I've gone back to several of my North American study sites -- they were just

crawling, literally teaming with lizards only 40 or 45 years ago, and now

they are parts of little cities, trailer parks, and not a lizard can be

found. Collections I made back then in storage in museums are really fossils.

They represent what was there before humans took over the habitat. To me that

is shocking. It makes those collections pretty valuable, too.

I'm not saying I don't approve of conservation biology -- Of course, we need

it -- but I'm saying if you consider yourself a determined conservation

biologist, please, please allow biologists access to the book of life. That's

got to be one of the main reasons for saving it.

Conservation biology is a crisis discipline. It's an emergency and it's a

man-made emergency. We wouldn't need it if we hadn't ravaged this Earth and

taken over so much of its surface. Right now, humans are using half of

Earth's land surface. Currently, we are using more than half of the available

fresh water. We are now using half of the solar energy that impinges upon the

land surface of the Earth. Worse yet, we have burned up fossil fuels that

took millions of years to form in a single century. That is shocking. One

species has taken half of everything for its greedy little self.

In physiological emergencies, we must intervene so we resort to surgery when

somebody's dying. War is the equivalent in political science. When you have

an international political emergency, you go to war. That's what conservation

biology is -- it's a crisis discipline -- it's man-made, just like war. We

wouldn't need conservation biology if we could control our own numbers.

"Wildlife management" is a pathetic joke, we humans cannot even

control our own populations!

Conservation biology is actually more than just biology because it bridges

the gap to the social sciences -- we have to start thinking in terms of the

ethics of what we do with planet Earth. We should have started thinking about

it a long time ago.

Problems in Conservation Biology

Recognition and management of endangered species

Restoration ecology

Ecosystem conservation

Ecological economics

Environmental ethics

Value of Biodiversity

Design of Nature Reserves

Minimum viable population size

Genetic bottlenecks

Population viability analysis

Sensitivity analyses of Leslie matrices

Here is a short list of some things conservation biologists are concerned

with -- they design nature reserves, identify endangered species, help to

prevent plants and animals that are teetering on the edge of extinction from

going extinct, and all sorts of other things. And this is well funded in

large parts of the world -- but this is not basic ecology -- it is applied

ecology. It's not reading the vanishing book, it's simply aimed at trying to

save what little is left. Money has to be spent on that. Nature reserves are

only temporary holding places, as witnessed by the continuing onslaught by

big oil on the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

When I was a little boy I spent hours and hours looking through "Audubon's

Birds of the World." I remember looking at the photograph of the last

Passenger Pigeon -- she died in a Cincinnati zoo in 1914. And as a little boy

I couldn't believe it, because I read the text -- it said the sky was

blackened with millions of these birds flying over. And then I read further

and found out that humans in their greed went up to their nests and clubbed

the babies and pickled them and shipped them off to Europe to be eaten as

squabs. They did this for a few seasons and managed to stop reproduction of

this species and effectively drive it extinct in a very short time -- a few

years. Extinction is forever.

When I first went to Africa to study lizards in

1970, rhinos were still fairly abundant and they hadn't been savaged by

humans. There are several species of rhinos and now all are endangered

because of a myth that came out of Asia that rhinoceros horns are an

aphrodisiac -- rhinoceros horn can be worth twenty thousand dollars a pound.

Rhinoceros are gone from most of their former geographic ranges. In some

areas, they are under 24-hour armed guard, and would be poachers are shot on

sight. The scales have tipped on the relative value of a human life versus

that of a wild animal.

Powerful people convince poor people living in third world countries that if

they could get them a rhino horn they'll pay a thousand dollars, which is

more than the potential killer could make in their entire life. Then the rich

guy gives him a gun and if the poacher succeeds, he buys it for a thousand

dollars, takes it to Europe or Asia, grinds it up and markets it for tens or

hundreds of thousands of dollars. Clearly, it's high time we switched to

Viagra. get them a rhino horn they'll pay a thousand dollars, which is

more than the potential killer could make in their entire life. Then the rich

guy gives him a gun and if the poacher succeeds, he buys it for a thousand

dollars, takes it to Europe or Asia, grinds it up and markets it for tens or

hundreds of thousands of dollars. Clearly, it's high time we switched to

Viagra.

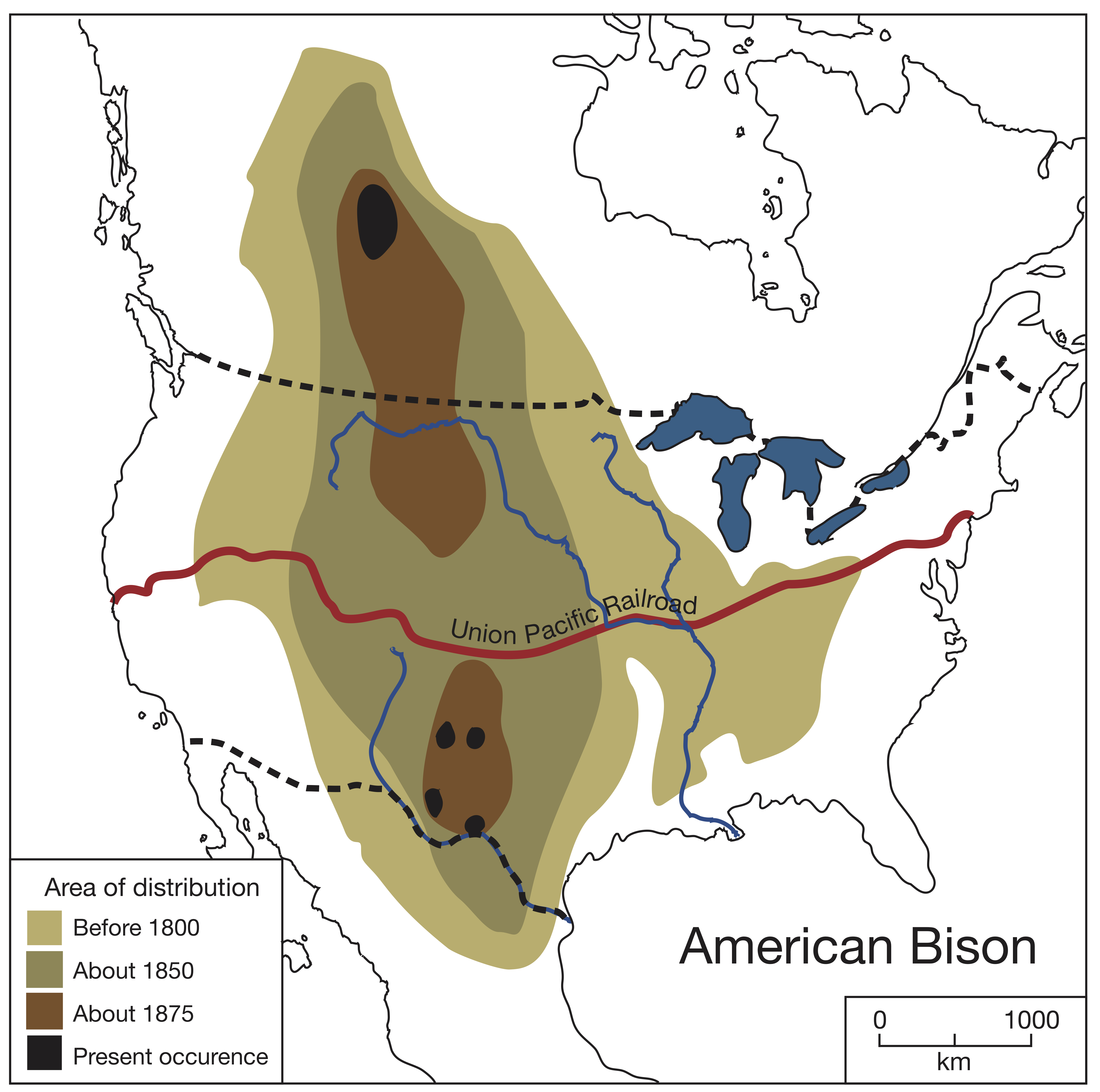

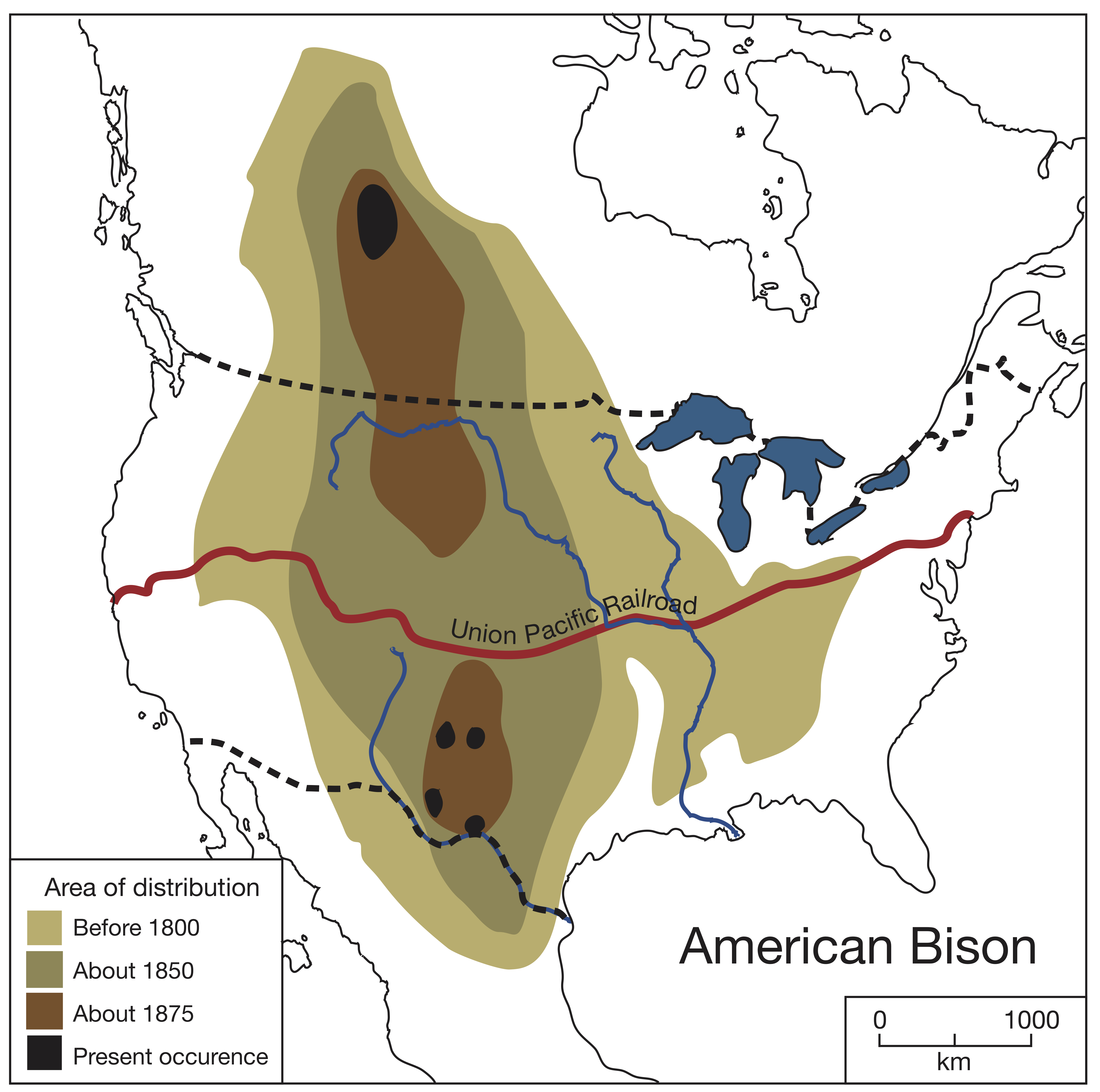

This is how we treat everything. Consider the history of the geographic range

of the American bison -- a very beautiful animal originally found from

Buffalo, New York, all the way to Sierra-Nevada before the 1800s. Huge herds

of untold millions were quickly culled. People back then told about bison

thundering all through the day and all through the night. They called it

"prairie thunder." But that's gone for good, and you're not going

to see or hear it in your lifetime, and that's a loss. When they built the

Trans-continental Railroad, people would buy a ticket and get a gun and load

it with big slugs and shoot bison as they rode across the continent, leaving

their carcasses to rot on the wide open prairie. As you can see, they split

the bison herd into northern herd and southern herd.

This is how we treat everything. Consider the history of the geographic range

of the American bison -- a very beautiful animal originally found from

Buffalo, New York, all the way to Sierra-Nevada before the 1800s. Huge herds

of untold millions were quickly culled. People back then told about bison

thundering all through the day and all through the night. They called it

"prairie thunder." But that's gone for good, and you're not going

to see or hear it in your lifetime, and that's a loss. When they built the

Trans-continental Railroad, people would buy a ticket and get a gun and load

it with big slugs and shoot bison as they rode across the continent, leaving

their carcasses to rot on the wide open prairie. As you can see, they split

the bison herd into northern herd and southern herd.

General Sheridan said that bison hunters had done more to control the

American Indian than all the cavalry put together. We basically starved out a

lot of American Indians -- those that we didn't kill instantly with smallpox

and measles. Our ancestors practiced genocide. We stole this continent from

other people. We just took it because we could.

I have a small herd of bison. They are absolutely magnificent animals. My

herd bull, Lucifer stands six feet tall and weighs about 2700 pounds -- when

Lucifer wants to, he goes over the fence -- and when he does (I've never

actually seen it), the earth must shudder at this spot for a little while. His

habit of jumping is how Lucifer earned his name.

We have to get off our

anthropocentric

high horse. Biodiversity has a value

beyond how it can be used by humans. Other Earthlings have been here longer

than us -- much, much longer -- and they have a right to this planet too --

that includes wasps that sting you, ants that bite you, scorpions and

rattlesnakes -- it includes wolves and wolverines and all kinds of animals

that we have pushed to very brink of extinction.

I cannot discuss all the things that concern conservation biologists but I do

want to point out one that it is kind of pathetic: we have settled on the

minimum viable population size -- how low can you go and still have something

-- to me, this is tragic.

One conservation biologist coined the term "extinction vortex" -- as we

drive populations down, so that they get precariously low, all kinds of

factors come together to sweep them down to extinction -- and all are

man-made. We stole their habitat. We fragmented their habitat. We've knocked

their population sizes down to the point where genetic variability disappears

-- and, don't forget, of course, climate change and toxic pollution. Quite

simply, to other inhabitants of Earth, humans are truly monsters.

We're more concerned now about toxic pollution as it affects humans. It's

causing cancers and feminization and all sorts of other maladies. But we

ought to be worried about it as it applies to everything on this earth. And

now, of course, people are finally, finally now beginning to be aware that we

have polluted the atmosphere to the point that the entire planet is changing.

It's only a matter of time now until the climate changes really drastically.

Some meteorologists have models that show thresholds ("tipping

points") where it shifts almost instantly overnight.

About 10,000 years ago, we made one of our worst mistakes (Diamond,

1987) -- we invented agriculture,

which allowed us to feed many more people and to reach unsustainable

population densities. We began to live in cities and invented money. Food

became a mere commodity that's bought and sold -- greedy people learned how

to make money on it. Most people lost touch with the reality of where food

comes from. When people go to the supermarket and can no longer find

Triscuits on the shelves they will wonder "Where did Triscuits come

from?" I fear that we will have to become hunter/gatherers again pretty

soon but Earth cannot support very many hunter/gatherers.

Triscuits on the shelves they will wonder "Where did Triscuits come

from?" I fear that we will have to become hunter/gatherers again pretty

soon but Earth cannot support very many hunter/gatherers.

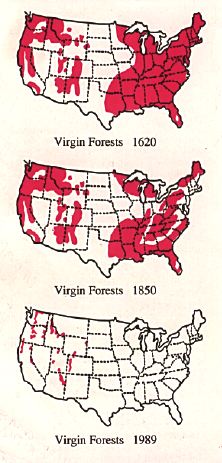

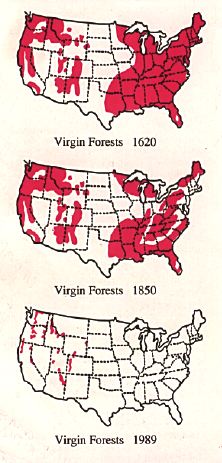

One of the things humans do is deforest everything -- we cut down trees to burn

to keep ourselves warm, build boats or houses. And

deforestation

has been pretty thorough in many places on the planet. The U.S. is fortunate -- we

still have the luxury of trees because we got into coal and fossil fuels

early and managed to keep ourselves warm and/or air-conditioned without

cutting down too many trees. Still, we have managed to cut down almost all of

the original native old growth American forests.

Out in the middle of nowhere in Northern Africa in the Sahara desert is an

oasis that had three big palm trees. It was called 'Three Trees' in Arabic.

But somebody cut those trees down, so although it is still on the map and it's

still an oasis, but there aren't any trees out there anymore. One cold night, a selfish

human cut them down and burned them to stay warm.

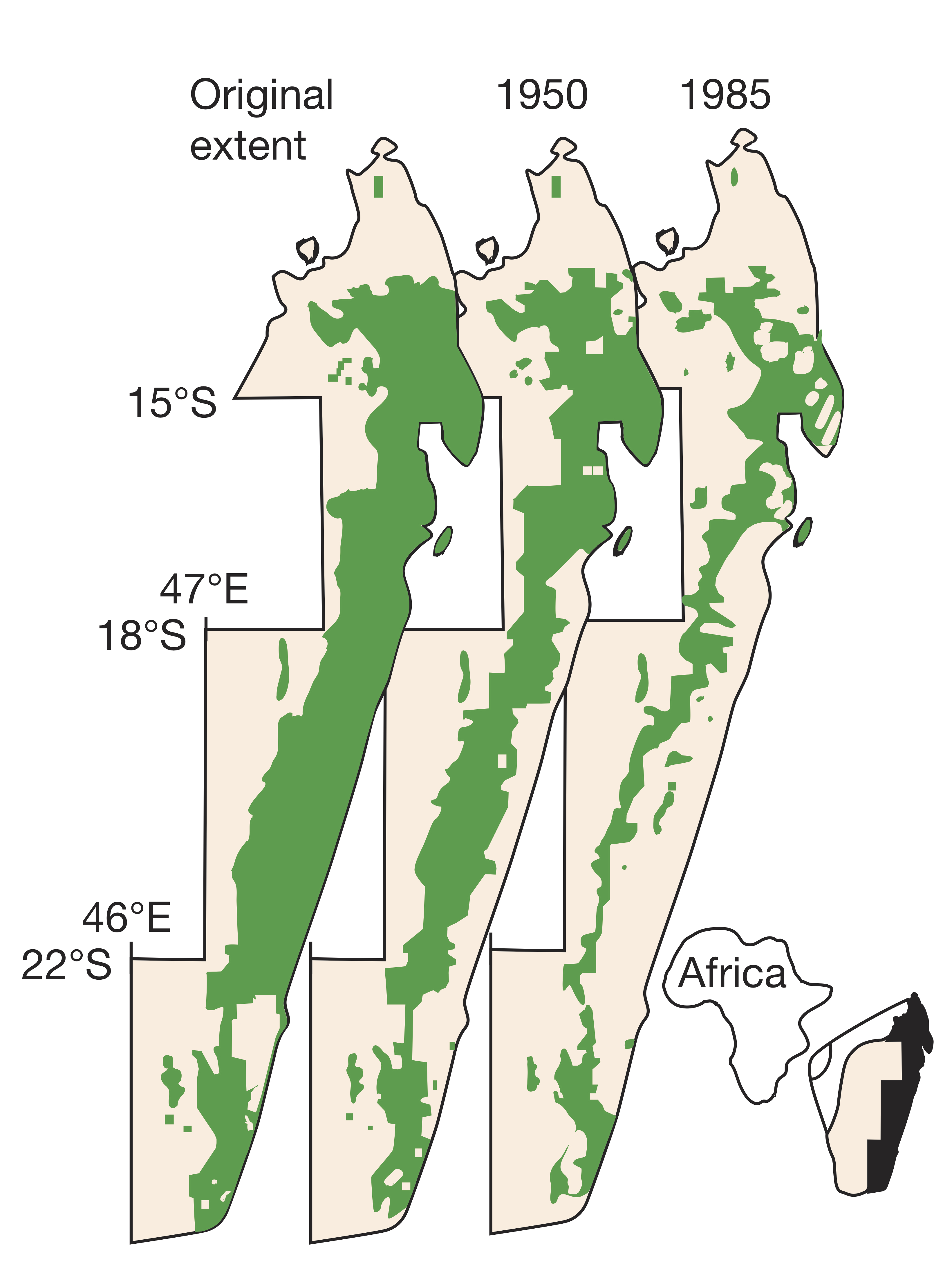

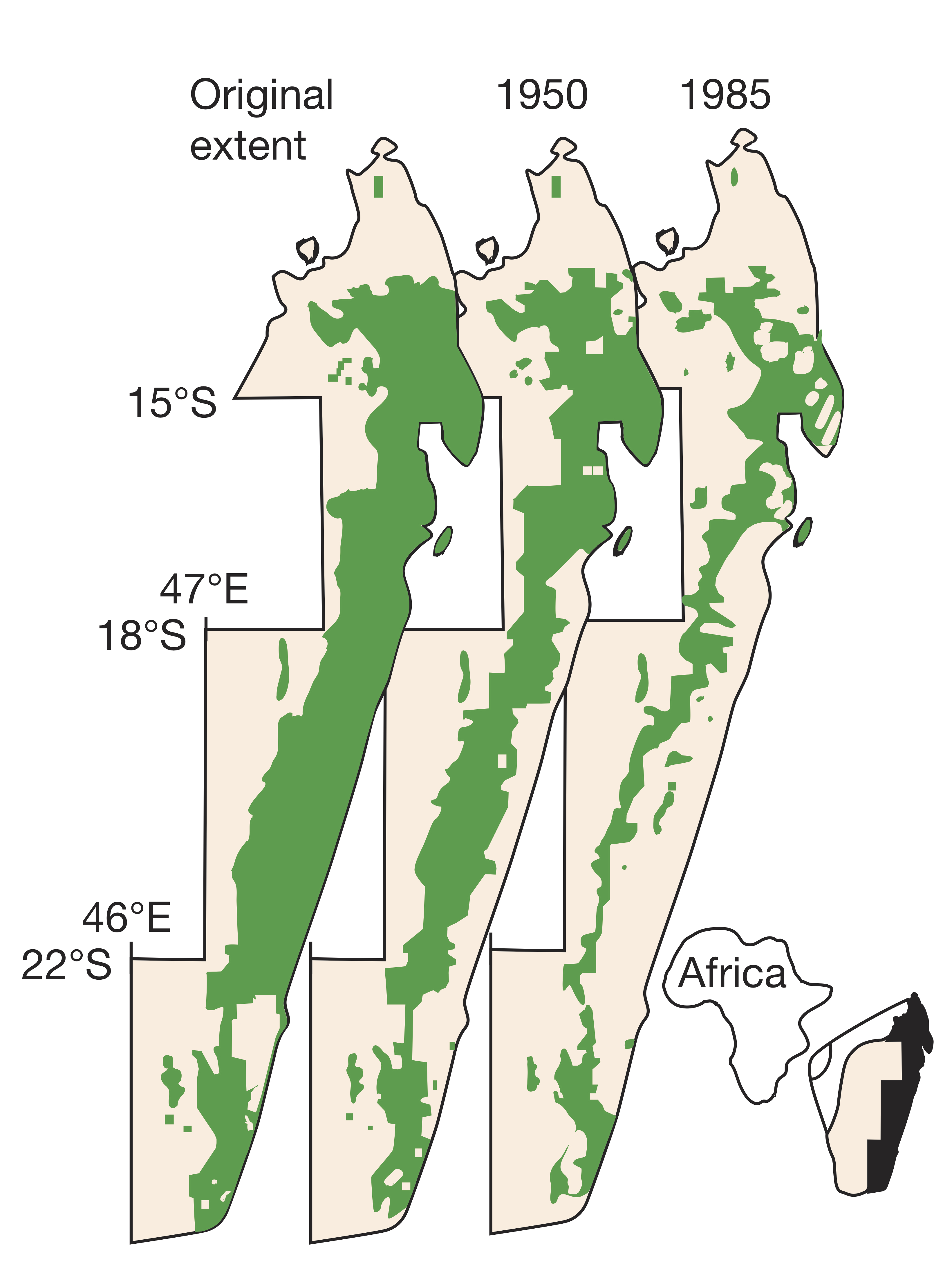

Madagascar is one of the places that I want to go before I die because it has so many

endemic species -- it split off from mainland Africa a hundred million years

ago and it's got all kinds of creatures that are found nowhere else on the

earth. Yet, the people of Madagascar are third-world, starving,

over-populated, eating everything. An endangered land tortoise in Madagascar

is highly protected on the world's list of "don't do anything to this

turtle," but they are commonly made into turtle soup by poor people in

Madagascar.

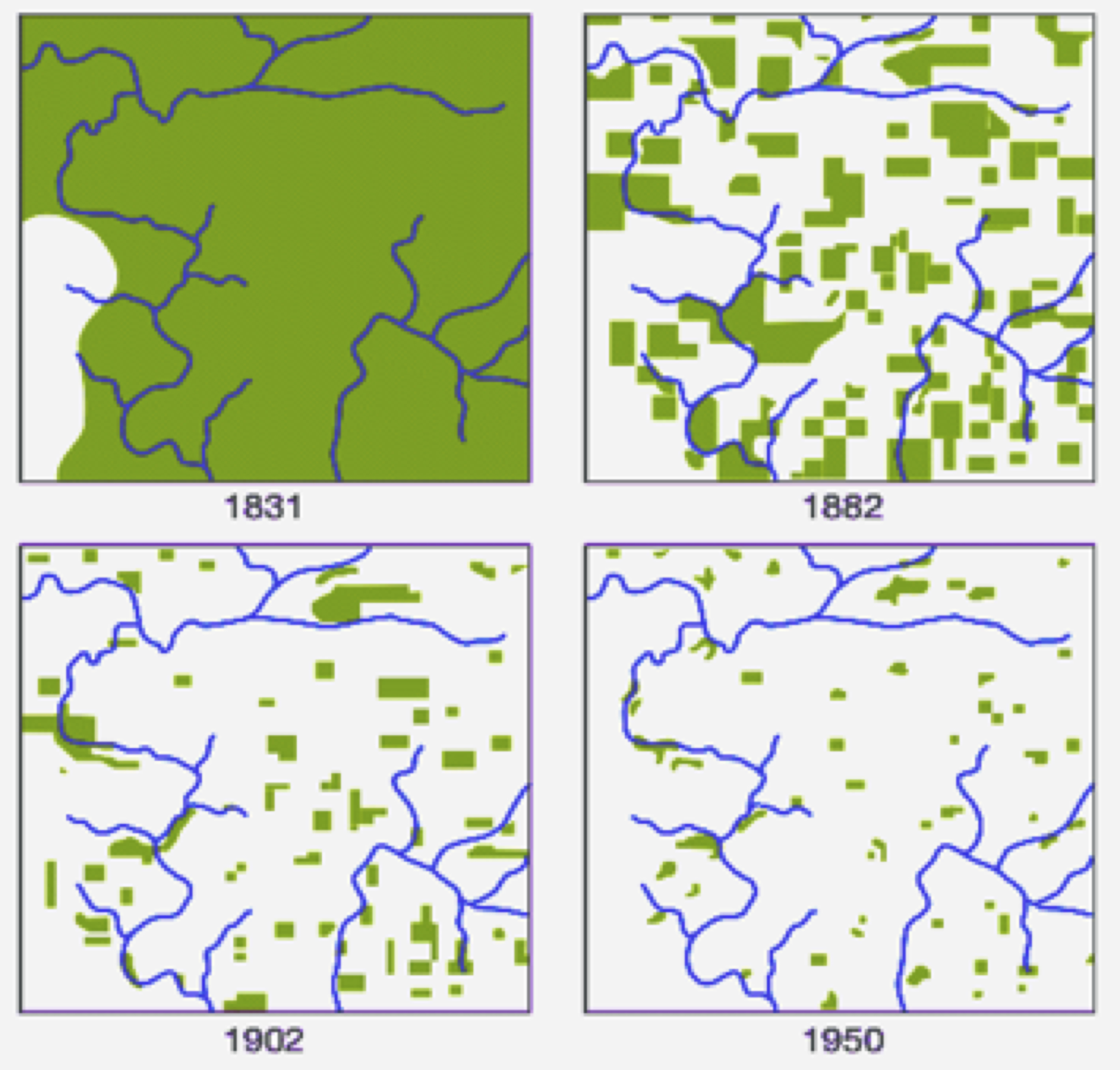

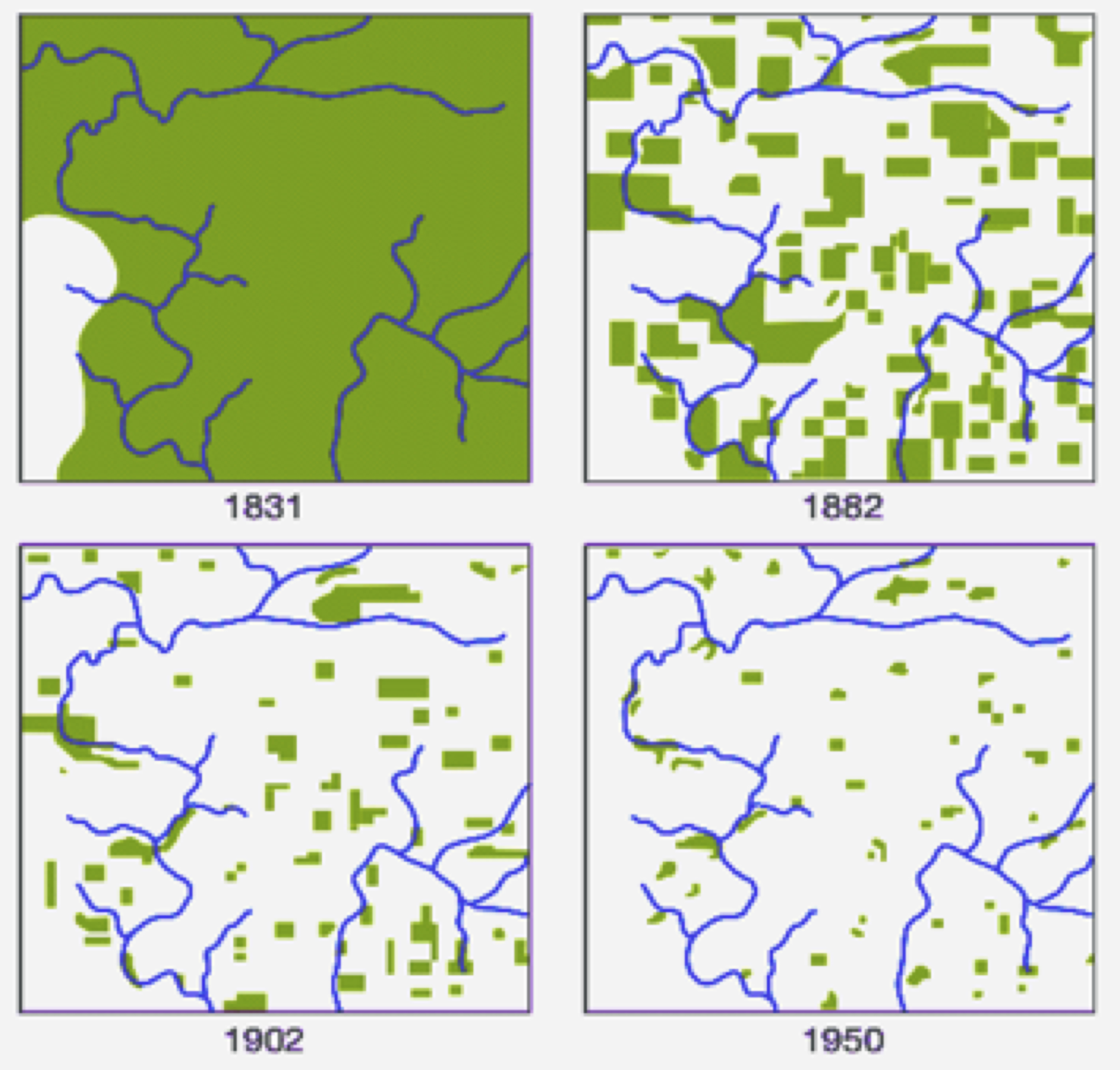

When humans first arrived in Wisconsin, a square mile was forested with a little piece of

prairie in the southwestern corner. The prairie burned every year (prairie

fires) and over the centuries the prairie built up deep black top soils,

which are nourishing our nation today. The first thing settlers did was cut

down the trees as you can see. In a little over a century, this was turned

into tiny wood lots. Imagine the effects this must have had on whatever used

to live in that forest.

Here's an example from Borneo. This is what we are

doing to this planet. Wood has become extremely valuable and we're

clear-cutting anything that's left.

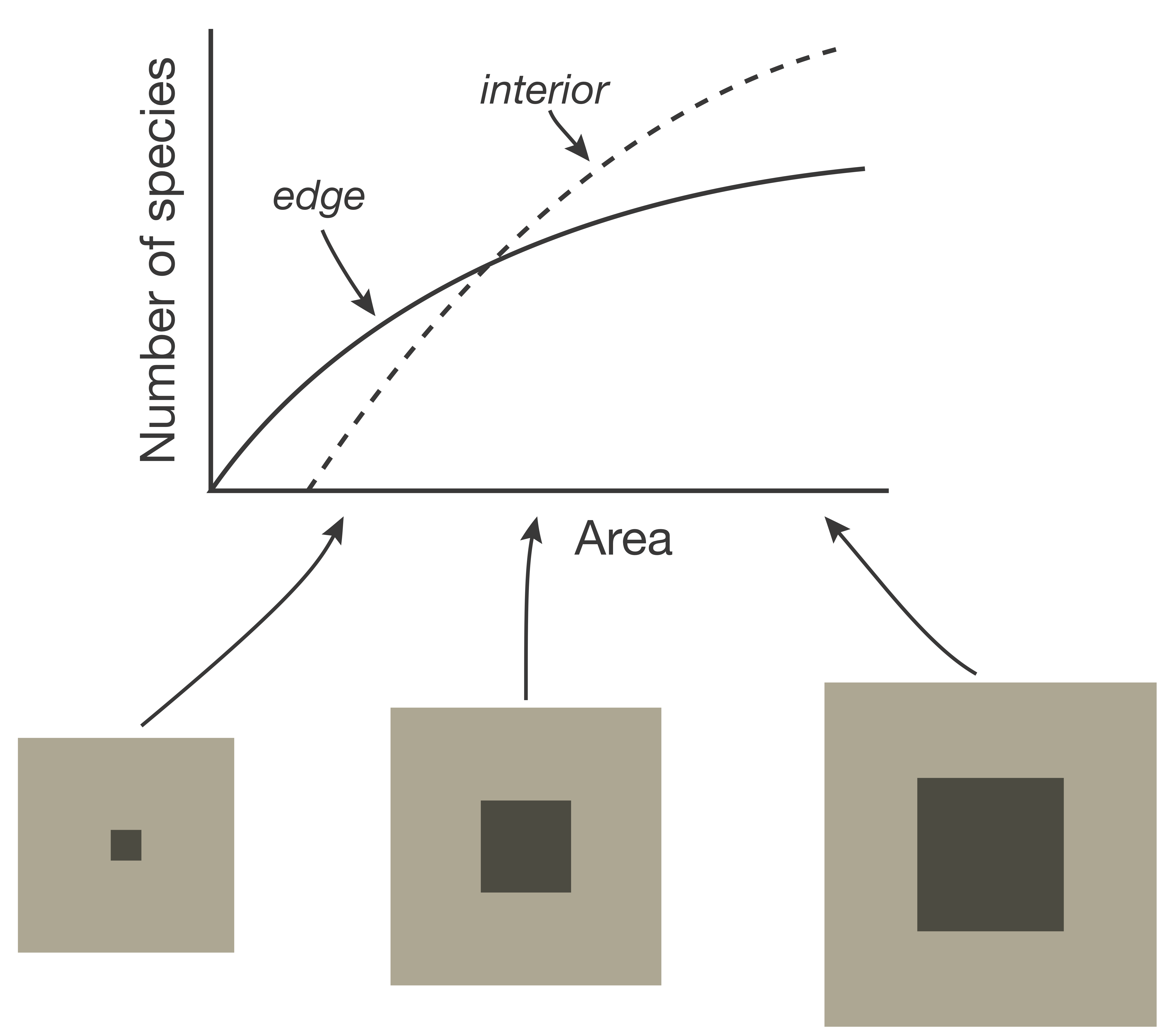

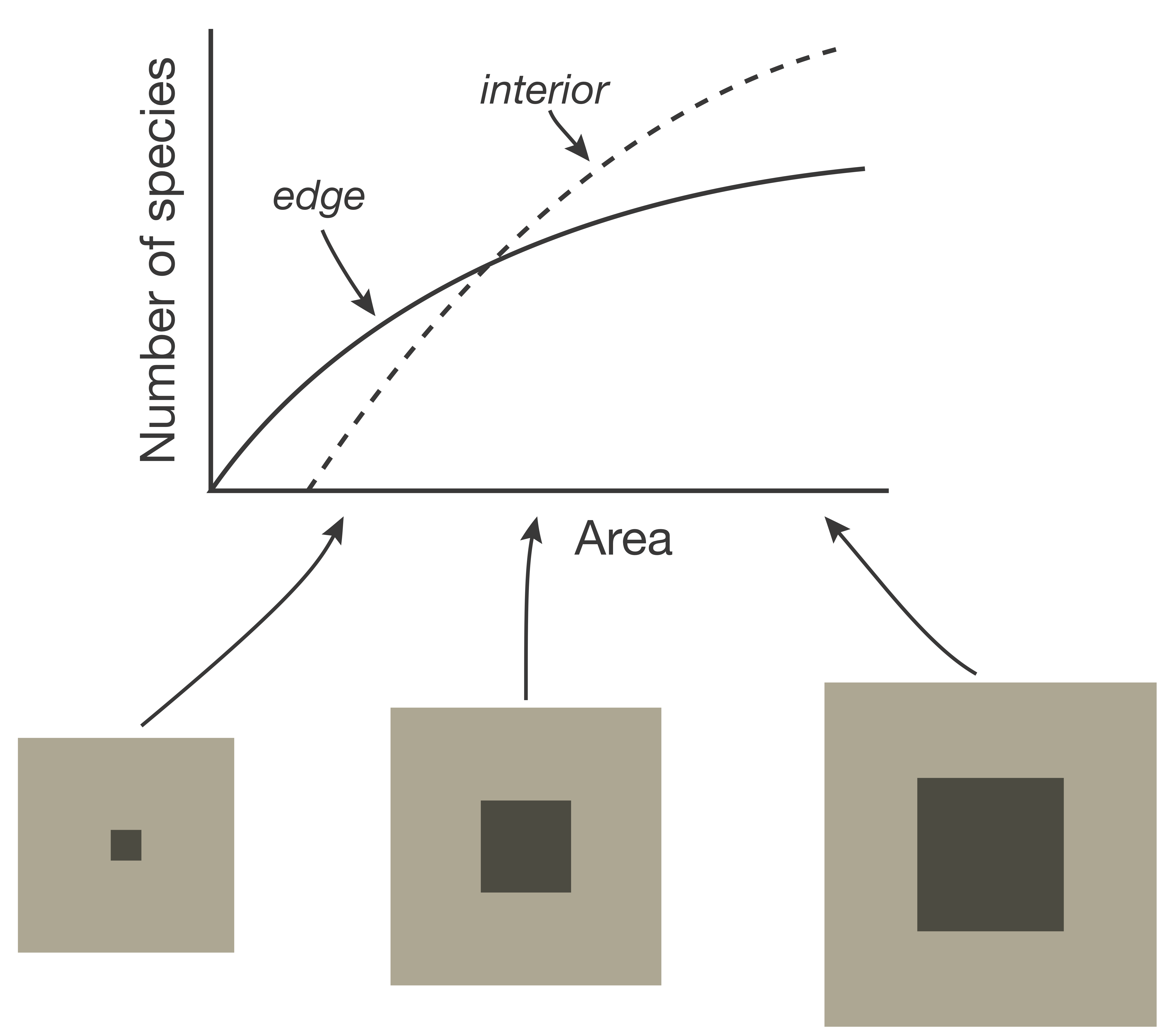

One of the problems with habitat fragmentation is that you lose core habitat. In that

scene that I showed you from Wisconsin back in the 1830s before humans got

there, there was only a little tiny bit of edge between the prairie and the

forest. Cowbirds lived along that edge. Cowbirds are brood parasites. They

lay their eggs in nests of other birds. Cowbirds used to be very scarce in

North America -- with habitat fragmentation, their populations have boomed

and the only place that small songbirds like warblers can lay their eggs now

to get away from these parasitic cowbirds is deep in the forest. When only

tiny little patches remain, a small songbird simply cannot escape from

cowbirds. Now cowbirds are very abundant, small songbirds are heavily

parasitized and their populations are on the brink of going extinct because

of our clearing and habitat destruction and fragmentation.

Here is more testimony to our anthropocentrism and human greed. This is the work of a

Texas company called Freeport-McMoRan. They have formed an alliance with

Indonesian officials, and they're taking gold and copper off the top of this

mountain in New Guinea (now part of Indonesia). They've stripped off most of

the top of that mountain and shipped it down the side in great big slurry

tubes that are ten feet in diameter to be sent back to smelters where they

extract the gold and copper. The ore goes down to the sea where it is hauled

away in ships.

You can see the damage this mining has done and is doing. It is causing huge

mudslides on the sides of the mountain and these are polluting once pristine

streams down below. Native tribes in the lowlands of New Guinea lived off

these beautiful, clear streams with fish and crustaceans and food of all

sorts -- now they can't get anything because the streams are clogged with mud

from dirt from Freeport McMoRan's mining operation on top of the mountain.

Some of these people being dispossessed by this greedy company on top of the

mountain broke into a supply shack and got some dynamite and primers and they

blew up the slurry tube. One of Freeport McMoRan's CEO's complained that it

was costing his company a million dollars a day not to have that slurry tube

open.

Freeport-McMoRan has been strip mining for ten years. They've been taking a

million dollars a day out of there for ten years. And, when they have exhausted

this mountain, no doubt they'll move operations to the next one behind

it.

This is the scariest graph that you're ever going to

see in your entire life -- take a good look at it. We hit six billion not

very long ago and now we are at six and a half and we're still going,

roaring. This kind of exponential population growth is unsustainable and has

to stop. People sometimes ask "what is the carrying capacity for

humans?" As I stated earlier, humans now occupy roughly half of Earth's

land surface, consuming over half the freshwater and using about half Earth's

primary productivity. However, lots of those people are living in poverty and

not even getting adequate nutrition. Many are just little babies, still

living under their parent's roof, who in a couple of decades, will need their

own houses and cars. A tidal wave of humanity is coming. No politician will

even recognize, let alone address, this enormous problem.

Now I'm going to try to convince you that human populations must be reduced.

Paul Ehrlich, in the 1960s, wrote a nice little book, "The Population

Bomb," calling attention to this. Nobody paid much attention to Ehrlich

(1968). Even today, I hear people saying, "Oh, I've heard you doomsday

ecologists before. We've still got water, there's no problem." They're

so short-sighted.

Consider China. How would you like to live there? Look at all those little

window A/Cs. They've got power, at least for now. Humans can really be packed

in. Do you want to live like a termite? Are we termites? Come on, I want to

be up on top of the hill where that chair is and I want to have some space

around me -- don't you? It's a matter of quality versus quantity of human

life.

People are in a state of denial -- they simply don't want to confront

reality. We still allow people to have more than two kids. We actually

encourage reproduction. You get a deduction for having kids. You should have

to pay more taxes when you have your first kid. When you have your second kid

you pay a lot more taxes, and when you have your third kid you don't get

anything back, they take it all. Our tax system is completely backwards. But,

then, so is our whole insane grow-grow-grow economic system. Earth and her

resources are finite.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife released caribou on the islands off of Alaska to

help the Eskimos, the Aleuts, get protein. Herds from these islands grew

exponentially just like the human population's been growing for quite a few

years until they ate everything they could eat and then the deer populations

crashed (Scheffer, 1951).

This is what's going to happen to us. This is going to happen in your

lifetime. Does that look like fun? Do you want to go there? You've already

gone there. We have waited too long.

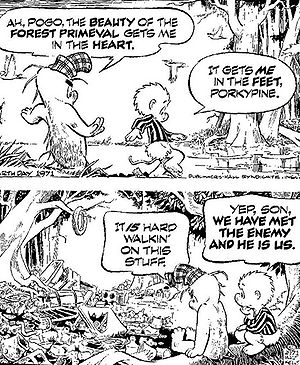

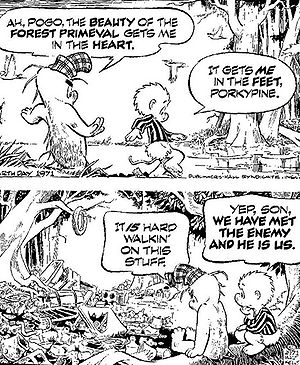

Cartoonists have had a lot of fun with this.

Consider Genesis. We've checked all the boxes, except one. We have dominion over the

fish and the fowl and everything that moves on this earth but we forgot,

forgot to replenish it. We just shriveled it up like that little dried up

raisin at the bottom -- we're sucking everything we can out of mother Earth

and turning it into fat human biomass.

Then, there's this Doomsday cartoon:

"I can't believe myself . . . I pass up salads,

only to buy a hotdog!

The looks I'm getting -- everyone knows what's in one of these! I can feel

their hot disapproval!

Hope you enjoy your meat! There goes another rainforest! Look, he's wearing

leather shoes, too! Assassin. Polluter!

Maybe if I stand absolutely still. Look at him standing there spewing out CO2!"

Everyone of us is guilty -- everything we do, every breath you take, every

time you take a shower or flush the toilet, every time you drive your car,

every time you buy anything we all contribute to the mess of pollution on

this earth. In many cases you don't even know what you're doing.

Carbon dioxide is turning out to be a big thing that could really spell out our

demise sooner maybe than many people think or realize. Big oil and

governments don't want you to know about this. CO2 has risen

steadily to almost double normal levels due to our burning fossil fuels and

cutting down and burning up forests. This has caused global

warming, and it's changing Earth's climates -- some even speculate that

it might be affecting things like earthquakes and hurricanes. Of course, the

more humans you pack in on the surface of the earth, the more such events are

going to decimate human populations.

Carbon dioxide is turning out to be a big thing that could really spell out our

demise sooner maybe than many people think or realize. Big oil and

governments don't want you to know about this. CO2 has risen

steadily to almost double normal levels due to our burning fossil fuels and

cutting down and burning up forests. This has caused global

warming, and it's changing Earth's climates -- some even speculate that

it might be affecting things like earthquakes and hurricanes. Of course, the

more humans you pack in on the surface of the earth, the more such events are

going to decimate human populations.

But, I'm a little more concerned about animals like

polar bears. Polar bears are big, warm and fuzzy -- the WWF cares about them,

and everybody thinks polar bears are nice and it would be a shame to lose

them. Polar bears require ice and ice floes. They're arctic adapted animals,

and as the ice floes melt, some people are thinking that it might be the end

of polar bears.

And, of course, those of you that haven't thought about this will say,

"Oh, we'll just keep them in zoos with the air conditioning turned way

down." Let me remind you that they are not wild polar bears; they are

like the words "love" trapped in senseless little vials.

So, global climate is changing, and I come back now to Paul Ehrlich. I said

this was going to go down, down, down and I meant it.

Ehrlich in the 1960s said, if humans don't have the political will to control

their own population, microbes will control our populations for us. Now I

want to remind you of 1300 AD when the "black death" swept down

from China and one-third of the world's population died.

We killed off an awful lot of indigenous new-world people with smallpox and

measles. These were things that white humans in Europe were adapted to

because we lived with them, but the people that made it across the Bering

Strait could not cope and a lot of those nasty microbes because of that.

We're going to see this again, but on a much bigger scale. Humans have been

very very lucky not to have experienced a worldwide plague for a long time,

and one is overdue.

Surrealistic Painting of industrialized man

(compliments of END.CIV

http://www.submedia.tv/endciv-2011/)

Microbes are small, and they reproduce very rapidly -- they have generation

times measured in minutes or less. They also evolve really quickly, and we

simply cannot keep up with them. We are doomed. The microbes are going to get

us. We are a great big emerging substrate just waiting for microbes to grow

on us. And even though we are still Homo sapiens -- sapiens means "smart" -- I'd say we're not. I'd say we're dumb

because we're letting our population grow just like bacteria grow on an agar

plate until they've reached the limits and used up everything; and that's

dumb. Humans are no better than bacteria, in fact, we are just like them when

it comes to using up resources. We need to use our brains to ease into a

sustainable existence, rather than merely breed our brains out.

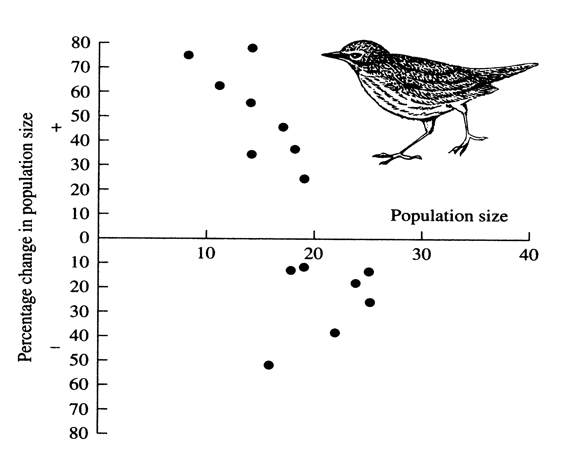

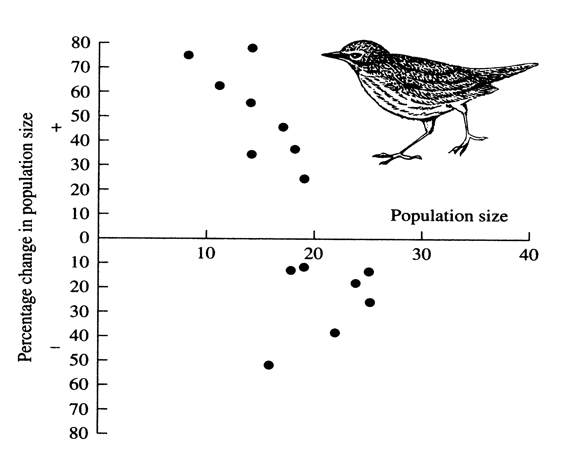

So, to try to convince you that populations are

regulated, I want to show you this plot -- a plot of the percentage change in

population size versus population density. When populations are large, they

tend to decrease and when populations are small they tend to increase. If the

slope of a regression line through those data points is negative, populations

are controlled through population regulation.

That plot was just one example. The table above

summarizes a hundred-plus others. Most of these studies were done with birds.

Birds have been well studied, but a few invertebrates are also included. To

the right you see significantly negative regressions, like the one I just

showed you, to the left are positive ones. The vast majority are negative,

and half of them are significantly negative.

There is just one conspicuous exception -- far, far off to the left -- one

species among these one hundred and thirty-eight thinks it can violate the rules

of the natural world and that it can grow indefinitely -- humans think they

are so smart that they can defy the rules. We are Homo the sap, not sapiens (stupid, not smart).

The Web is such a wonderful place. I thought, what would really jostle the audience?

And I thought of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, and so I typed that in

-- somebody spent days painting this for us.

That's Conquest in front, then War, Famine, with

Death bringing up the rear. If humans don't go out in a blaze of nuclear

holocaust, or starve in a massive famine, death by a lethal pandemic seems a

likely prospect.

Then I typed in "skull" and got this, complete with flashing red eyes. Great, eh? Death awaits us all.

Think about everything I've said and more.

This is an AIDS-infected T-cell of a human. Each of those little round things

is an HIV virion that can infect a new human. Basically, this virus uses our

T-cells as factories to make copies of itself. HIV is a pandemic spread

worldwide. It's increasing in frequency in a lot of places and it's a big

concern to everybody. But, it's not going to be the one that gets us because

HIV acts too slowly, it lets us live several years while it passes itself on

to new hosts. HIV works too slowly to control human populations.

Now let's consider some other viruses -- Ebola zairehas potential. It kills nine out of ten humans, and

quickly, within a few days. It's never gotten out of Africa because it is so

virulent it kills everybody before they can move.

You can only catch Ebola zaire

by direct contact with a human who is infected. It causes you to bleed. It

breaks capillaries and you bleed out your orifices and if you touch somebody

who's sick with it you get it and you die, too -- nine times out of ten.

Another variety of Ebola, Ebola

reston did get out of Africa and

into the U.S. in the form of green monkeys imported for medical research --

it's named after Reston, West Virginia where there is a quarantine facility

for these monkeys. All the monkeys died in an epidemic without any contact

with each other. The monkeys were sharing a common ventilation system in a

room, with recirculating air. All the monkeys in that room that breathed the

same air caught the virus and died. It was airborne transmission between

hosts. Luckily for us, Ebola reston

doesn't infect humans.

Now it is only a matter of time until Ebola zaireevolves and mutates a little, it will eventually

become airborne, and then we might finally see it spread. And if and when it

finally does, it will sweep around the world -- we're going to have a lot of

dead people. Every one of you lucky enough to survive will get to bury nine.

Think about that. If it isn't Ebola that gets us, another virus will (Nee, 2005).

Did you ever wonder why things like SARS and now the Avian Flu are continually cropping up?

They're arising because we were dumb enough to make a perfect epidemiological substrate for

an epidemic. Instead of using our brains to keep our one and only spaceship habitable,

we bred our brains out and destroyed its life support systems,

and now we're going to have to pay for it. The microbes are going to take over.

They're going to control us again as they have in the past. Think about that.

Humans could have been stewards of Earth and all its many denizens, microbes,

plants, fungi, and animals. We have the ability to have been God-like.

Instead, for a short-sighted and selfish transient population boom, we became

the scourge of the planet. We wiped out and usurped vast tracts of natural

habitat. We ate any other species that was edible and depleted Earth's

multitude of natural resources. In a single century, humans burned and wasted

fossil fuels that took millions of years to form. We fouled the atmosphere,

polluted the waters, and damaged all of our one and only Spaceship's life

support systems. The disparity between what humans could have been versus the

pitiful creatures we actually managed to become is tragic and unforgivable.

If only more people would live up to their full potential!

Part Two

Now, here's a breath of fresh air: Aldo Leopold (1949). This is the start of

the tiny little up. We've been to the lowest of the low where the microbes

are going to get us. Now, I'm going to try to be a little bit more

optimistic. Aldo Leopold was one of the first conservation biologists. He was

in wildlife management at the University of Wisconsin back in the 1950s.

Leopold died young, but his children have put together a collection of his

essays into a small book, "A Sand County Almanac." I encourage all

of you to read it. Some of the things he describes in this little book bring

tears to my eyes. I mean I literally break down and weep.

One of the profound things Aldo Leopold said was

that each generation doesn't even know what has been lost -- only previous

generations remember. "Perhaps our grandsons, having never seen a wild

river, will never miss the chance to set a canoe in singing waters."

When I was a boy, I could walk out my back door to a semi-pristine creek and

catch snakes and lizards. Kids these days simply don't have that opportunity.

There aren't any pristine creeks anymore and they're living in cities, and

that's unfortunate. I became a biologist largely because of my exposure to

wild animals when I was young.

One of Leopold's statements was that we cannot continue to act as conquerors

-- we weren't given some God-given right to do anything we want like chop

down redwood trees -- we must have respect for fellow inhabitants of this

earth. We need to transcend anthropocentrism. Other Earthlings have a right

to this planet, too.

This figure is from a conservation biology textbook, it's very appropriate these days.

Once we lived in small little tribes in caves -- cave men kept around a few

elders for their wisdom -- because they had lived through droughts and solved

other problems. For example, old guys might know how to treat a broken leg or

some illness. And, of course, medicine men and women specialized in such

information.

At the end of the Pleistocene, just 10,000 years ago, only about 500

generations before now, humans were hunter/gatherers, living off the land in

small bands or tribes. We had no electricity, no cars, and no supermarkets,

let alone fast food joints. We did not live in houses, but found refuge in

caves and crude shelters. We hunted animals with spears, bows and arrows, and

nooses. We caught fish with crude nets and fish hooks made from sharp pieces

of bone. We gathered nuts and berries. We used sinew as twine and made our

own ropes. We had no jeans or shirts, underwear, or toilet paper -- we

clothed ourselves in animal skins and furs, and wiped ourselves with leaves.

We had no television but sat around campfires telling one another stories and

passing on vital information from one generation to the next (this was the

origin of human

knowledge). Survival through the ice ages and winters in the temperate

zones was no easy feat under such conditions, requiring substantial advanced

preparation and food storage, as well as no small amount of good luck.

Tribes probably defended territories against other small bands of humans, but

must have occasionally exchanged members. Our primitive hunter/gatherer

ancestors must have enjoyed a good life during times of plenty in spring and

summer when food supplies were bountiful. There was limited

"ownership" of such resources, and people could help themselves to

whatever they could find. Money had not yet been invented and food was

essentially free for the taking. Many fewer humans dwelled on Earth then, and

the planet could easily supply their needs.

Things are very different today -- demand for limited resources now greatly

exceeds supply, and virtually everything is claimed as "owned" by

someone else. As their populations burgeoned, humans invented agriculture and

money, and made the transition from being cave men and women to modern

civilized urbanites quite rapidly. Many of our behaviors and instincts,

once suitable for a caveman's existence, such as greed and revenge, became

anachronous, even dangerous.

We lived in little inbred groups and occasionally people would move between

caves but these family groups were little tribes that battled over resources.

That's at the bottom of this figure. We're all familiar with selfish behavior

in those small circles at the bottom. We're all selfish and natural selection

favors selfish behavior. You can be altruistic towards your kin, as long as

they share genes that are identical by descent.

Cavemen tribes prospered, but now as we expand outwards to less closely

related individuals and to larger social groups, finally to races or entire

nations, altruistic behavior vanishes.

Look at the polarization in America today -- 50 percent one way and 50

percent the other. We are not doing very well at cooperating as we go outside

of that tiny circle to larger and larger domains such as dealing with people

in other nations with different belief systems. We need to engage in dialogue

and communicate and change each other's minds. All of us need to consider the

health of the entire Spaceship

Earth.

Going still farther out, you get to individuals of other sentient species. Here I'm

thinking of chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans. They're our closest relatives. They

share our blood groups. They probably can think. If one of those species had

been the lucky one to inherit the earth and evolve the big brain and take

control over everything else, how they would be treating us? We might be in

cages -- they'd be using us for medical experiments and eating humans like we

now eat gorilla "bush meat" in Africa. Think about that.

Actually this goes beyond gorillas and apes to the entire earth. Humans need

to become responsible stewards of this planet rather than remain mere

conquerors and rapists.

Here's one more little upbeat thing, but unfortunately this isn't very much

of an up, Herman Daly has identified the big problem, which is our economy. It's

basically completely flawed. You've heard politicians talk about

"growing the economy." Our economy is based on the principle of a

chain letter, a pyramid scheme. That simply cannot work. Upside down pyramids

must fall over. Bubbles always burst and this bubble is bursting.

It's bursting right now in terms of fossil fuels. The price of gasoline isn't

going to go down again. Some greedy oil men are getting very rich from peak oil.

We have institutionalized greed in the form of limited liability offshore

corporations -- if we do not control runaway greed, it will destroy us all.

You need to hone your survival skills.

On your way home tonight, stop and get a real tarp, one that's made out of

waterproof canvas. Don't get one of those crummy plastic ones -- they

deteriorate too fast. Start packing it with the absolute necessities you must

have to stay alive. These would include things like needles and thread, a

blanket, some sharp knives, pliers and wire, water containers, some string,

rope, and twine, among other things.

I'm not talking toothpaste. I'm not talking about a lot of things. Wrap them

up and figure out how you can carry it on your own two shoulders because you

are not going to be able to take public transport or drive your car when

civilization finally collapses. You will need to get as far away as you can

from any other human beings because they will take your stuff away from you.

Try to snare a rabbit, if there is still a rabbit out there to catch. And,

when you catch that rabbit, skin it and tan its hide (learn how to use

tannins to tan hides -- soon you'll be wearing one!)

Our economic system based on continual growth must be replaced by a

sustainable system where each of us leaves the planet in the same condition

that it was in before we were born. This will require many fewer of us and

much less extravagant life styles. We won't be able to move around so freely

(airplanes will become a thing of the past) and we will have to go back to

walking and riding horses. In addition, humans will have to be more spread

out, living without big cities. Before it is all over, we are going to have

to limit our own reproduction, un-invent money, control human greed, revert

back to trade and barter, and grow our own crops, among other things.

Let's get back to Herman Daly. He wants us to live in a sustainable world,

and he has the idea of an equilibrium economy. Solzhenitsyn (1974) had the

same idea. In an equilibrium economy, every one of us would leave this earth

in exactly the same shape it was when we came into it. None of us are doing

that. None of us.

Mainstream economists think Daly is some kind of a nut, they just ignore him.

The economists that advise our political figures have relied completely on

grow, grow, growthmania -- impossible voodoo economics.

They place no value on wilderness and actually assume that resources are infinite!

Read Nadeau's

"The Economist has No Clothes".

So, if you have a leaning towards economics, here's a challenge for you.

Economics must be reinvented. Herman Daly published four books on

equilibrium, or sustainable, economics. Others must join him. People must

stop denying reality and think. They can't just keep behaving like sheep thinking resources are

ever expanding. We've got to realize that per capita shares of resources are

ever contracting, and we're running out of everything that matters -- oil,

food, land, clean air and water.

Meadows et al. wrote a book on some of this, actually, three versions. The

first one was commissioned by some people concerned about the environment

back in the 1970s. Dennis Meadows was the first author and it was called

"Limits to Growth" -- they developed a systems model for the earth

and its resources and how many people the planet can support. They worked

through various scenarios including unlimited technology and many other

things. Of course, big oil and some fools still claim that we will keep

finding new supplies of oil and keep on going. I cannot understand people who

refuse to face the fact that the world is finite.

Notice the estimated population curve with a collapse -- things are going to

get better after the collapse because humans won't be able to decimate the

Earth so much. And, I actually think the world will be much better off when

only 10 or 20 percent of us are left. It will give wildlife a chance to

recover -- we won't need conservation biologists anymore. Things are going to

get better for the other denizens of Earth as they deteriorate for humans.

Technology lures us out on to thin ice. I learned this years ago, when I got

my first 4-wheel drive vehicle. Thinking that now I could go anywhere, I soon

discovered that you get stuck using four wheels, too, but much worse than you

can get stuck with two-wheel drive (a Land Rover stuck up to its axles in

deep mud is sad to contemplate!).

Unlimited cheap clean

energy, such as

that so ardently hoped for in the

concept of cold fusion, would actually be one of the worst things that could

possibly befall humans. Such energy would enable well meaning but uninformed

massive energy consumption and habitat destruction (i.e., mountains would be

leveled, massive water canals would be dug, ocean water distilled, water

would be pumped and deserts turned into green fields of crops). Human

populations would grow even higher and the last vestiges of natural habitats

would be destroyed. Heat dissipation would of course set limits, for when

more heat is produced than can be dissipated, the resulting thermal pollution

would quickly warm the atmosphere to the point that all life is threatened,

perhaps the ultimate ecocatastrophe. Read the

Weakest Link.

In 1972, Meadows basically said, we better do something fast. And, of course,

like all of us who grew up in the 1960s, people were in denial and nobody

paid any attention. We just kept breeding our brains out and ignoring it.

Then in 1992 they wrote a second book called "Beyond the Limits,"

in which they pointed out that we could never ease back into a sustainable

society, that we had already gone too far in 1980.

Now it's 30 years later and, with his daughter, Donella, and Jorgen Randers,

Meadows has put out "Limits to Growth -- The 30 year Update." This

is quite a depressing book because in every scenario they run, humans must

experience collapse. Collapses are worse in some scenarios than in others,

but we must face all in the immediate future.

You are going to see it in your lifetime and the important thing is this is

just the beginning, this peak oil/peak food problem we are experiencing right

now. We aren't prepared for a what's coming and we cannot avoid it. The

future is coming up on you fast -- if you are fortunate enough to survive,

you are going to become a hunter-gatherer. Get prepared for that.

Here's a graph comparing Earth's carrying capacity for humans to our human footprint:

the horizontal dashed line is the carrying capacity and the solid black one

represents resources used by our actual population -- you can see we crossed

the maximum level about 1980, and in 1999 we were more than 20 percent above

according to their estimate (it's probably at least 25% now).

This graph is overly optimistic because we could never have reached six-and-a-half

billion without fossil fuels. Basically, we turned oil into food and food

into humans, and we used the oil to build highways and cars and take over and

make this mess -- the carbon dioxide pollution and all the rest. But now

we're running out of fossil fuels and haven't invested enough in developing

renewable resources, especially solar energy.

So this is really a very exciting time in the history of mankind. Remember

that ancient Chinese curse: "May you live in interesting times"?

Right now has got to be just about the most interesting time ever and you get

to see it. Hopefully, a few of us will live through it.

I recommend Heinberg's "The Party's Over. Oil, War and the Fate of

Industrial Societies" -- a chemist once told me, "it's like we were

on a luxury liner and we're on the upper floor of the ship and there's a hole

in it and it's sinking, but everybody's having a big party up here, and it's

just a matter of time until we are all underwater." This is Heinberg's

message -- he carefully researched all the facts. It's a doomsday book but

he's an optimist so he has this optimistic end where he lays out what we can

do, as individuals, if one is to live lightly on the land, you know, lessen

your footprint -- drive a Prius instead of an Excursion -- it'll save you

money -- ride a bicycle -- grow your own food. He has all kinds of good

ideas. Unfortunately, even if you do all you can to minimize your own

footprint on Earth, many others won't. Cleaning up the trash along highways

merely makes things seem better and fosters litterbugs.

I recommend Heinberg's "The Party's Over. Oil, War and the Fate of

Industrial Societies" -- a chemist once told me, "it's like we were

on a luxury liner and we're on the upper floor of the ship and there's a hole

in it and it's sinking, but everybody's having a big party up here, and it's

just a matter of time until we are all underwater." This is Heinberg's

message -- he carefully researched all the facts. It's a doomsday book but

he's an optimist so he has this optimistic end where he lays out what we can

do, as individuals, if one is to live lightly on the land, you know, lessen

your footprint -- drive a Prius instead of an Excursion -- it'll save you

money -- ride a bicycle -- grow your own food. He has all kinds of good

ideas. Unfortunately, even if you do all you can to minimize your own

footprint on Earth, many others won't. Cleaning up the trash along highways

merely makes things seem better and fosters litterbugs.

Educated people tend to have fewer children than uneducated people. Garret

Hardin (1964, 1998) pointed this out, and said those who don't have any

conscience about the Earth are going to inherit the planet, because those who

don't care are leaving more progeny than those who do care and make fewer

babies. And so human conscience is on its way out, if we persist on our

present course, we're going to evolve into uncaring

humanoids. That's probably already happening and cognitive abilities are

falling for the same reasons, too (Herrnstein, 1989).

To conclude, I want to quote John Stuart Mill (1859) to point out that bright

people have seen this coming for a long, long time:

"I cannot . . . regard the stationary state of capital and wealth with the unaffected aversion so

generally manifested towards it by political economists of the old school.

I am inclined to believe that it would be, on the whole, a very

considerable improvement on our present condition. I confess I am not

charmed with the ideal of life held out by those who think that the normal

state of human beings is that of struggling to get on; that the trampling,

crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other's heels . . . are the most

desirable lot of humankind . . . It is scarcely necessary to remark that a

stationary condition of capital and population implies no stationary state

of human improvement. There would be as much scope as ever for all kinds of

mental culture and moral and social progress; as much room for improving

the Art of Living, and much more likelihood of its being improved" (my

italics).

Mill wrote that almost 150 years ago -- it's basically a statement about how a

stationary world can be a good world. In a stationary world you don't have to

worry about bubbles bursting, losing your stock, running out of oil, or

survival kits. A stationary world is sustainable and the world stays the same

from day to day.

We've got to reign in runaway greed -- we could live in a stationary world as

opposed to one that's based on growthmania where everybody has to elbow the

other guy and compete to get to the front and be concerned about who's going

to win and who's going to lose every day in the stock market. In a stationary

world, we can focus in on things that really matter -- I love Mill's phrase

"the art of living." Let's get to work on improving the art of

living.

References

Carson, R. 1962. Silent Spring.

Houghton-Mifflin. [reprinted in 2002]

Catton, W. R. 1982. Overshoot. The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary

Change.

University of Illinois Press.

Colburn, T., D. Dumanoski and J. P. Myers. 1996. Our stolen future. Dutton.

Daly, H. E. 1991. Steady-State Economics. Island Press, Washington, D. C.

Daly, H. E. 1997. Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development.

Beacon Press

Daly, H. E. and K. N. Townsend (eds.) 1993. Valuing the Earth: Economics,

Ecology, Ethics. M. I. T. Press.

Diamond, J. 1987. The Worst Mistake

in the History of the Human Race.

Discover Magazine, May 1987, pp. 64-66.

Ehrlich, P. 1968. The Population Bomb. Ballantine

Hardin G. 1968.

The tragedy of the commons.

Science 162:1243-1248.

Hardin, G. 1998. The Feast of Malthus. Living within Limits. The Social

Contract.

Heinberg, R. 2003. The Party's Over: Oil, War, and the Fate of Industrial

Societies.

New Society Publishers.

Herrnstein, R. J. 1989. IQ and falling birthrates. The Atlantic, May 1989

v263 n5 p72(7)

Leopold, A. 1949.

A Sand County Almanac.

Oxford University Press.

Meadows, D. H., J. Randers, and D. Meadows. 2004. Limits to Growth:

The

30-year Update. Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

Mill, J. S. 1859. On Liberty. Ticknor and Fields, Boston.

Nadeau, R. 2008.

The Economist Has No Clothes.

Scientific American

Nadeau, R. 2008.

Brother, Can You Spare Me a Planet?

Scientific American

Nee, S. 2005. The Great Chain

of Being . Nature 435: 429. . Nature 435: 429.

Pianka, E. R. 2000. Evolutionary Ecology. Sixth Edition. Benjamin-Cummings,

Addison-Wesley-Longman. San Francisco. 528 pp.

Pianka E. R. 2006.The Human Overpopulation Crisis

Pianka, E. R. 2007.

Can Human Instincts be Controlled?

Rolston, H. 1985. Duties to endangered species. BioScience 35: 718-726.

Scheffer, V. B. 1951. The Rise and Fall of a Reindeer Herd. Science 73:

356-362

Solzhenitsyn, A. I. 1974. Letter to the Soviet Leaders. Harper and Row.

Thoreau, H. D. 1893. Walden.

Download a pdf copy of The Vanishing

Book of Life

|

The great early American naturalist Henry David Thoreau embraced wilderness and used a

book as a metaphor for life on Earth. Philosopher of science Holmes Rolston III extended

Thoreau's metaphor as the "vanishing book of life." Rolston (1985) remarks "destroying

species is like tearing pages out of an unread book, written in a language humans hardly

know how to read." This book of life is disappearing before our eyes. Each page corresponds

to one of the many species of life forms that lived or still lives on Earth, and describes

everything one could possibly want to know about its natural history and ecology, its

parasites, prey, and predators, how it is related to its closest ancestors, as well as

much more. Each chapter, in turn, describes how every member of this myriad of millions

of different microbes, fungi, plants, and animals interact within a particular natural

ecosystem. All of Earth's once pristine ecosystems, past and present, are thus described,

metaphorically, in many volumes.

The great early American naturalist Henry David Thoreau embraced wilderness and used a

book as a metaphor for life on Earth. Philosopher of science Holmes Rolston III extended

Thoreau's metaphor as the "vanishing book of life." Rolston (1985) remarks "destroying

species is like tearing pages out of an unread book, written in a language humans hardly

know how to read." This book of life is disappearing before our eyes. Each page corresponds

to one of the many species of life forms that lived or still lives on Earth, and describes

everything one could possibly want to know about its natural history and ecology, its

parasites, prey, and predators, how it is related to its closest ancestors, as well as

much more. Each chapter, in turn, describes how every member of this myriad of millions

of different microbes, fungi, plants, and animals interact within a particular natural

ecosystem. All of Earth's once pristine ecosystems, past and present, are thus described,

metaphorically, in many volumes.

get them a rhino horn they'll pay a thousand dollars, which is

more than the potential killer could make in their entire life. Then the rich

guy gives him a gun and if the poacher succeeds, he buys it for a thousand

dollars, takes it to Europe or Asia, grinds it up and markets it for tens or

hundreds of thousands of dollars. Clearly, it's high time we switched to

Viagra.

get them a rhino horn they'll pay a thousand dollars, which is

more than the potential killer could make in their entire life. Then the rich

guy gives him a gun and if the poacher succeeds, he buys it for a thousand

dollars, takes it to Europe or Asia, grinds it up and markets it for tens or

hundreds of thousands of dollars. Clearly, it's high time we switched to

Viagra.  This is how we treat everything. Consider the history of the geographic range

of the American bison -- a very beautiful animal originally found from

Buffalo, New York, all the way to Sierra-Nevada before the 1800s. Huge herds

of untold millions were quickly culled. People back then told about bison

thundering all through the day and all through the night. They called it

"prairie thunder." But that's gone for good, and you're not going

to see or hear it in your lifetime, and that's a loss. When they built the

Trans-continental Railroad, people would buy a ticket and get a gun and load

it with big slugs and shoot bison as they rode across the continent, leaving

their carcasses to rot on the wide open prairie. As you can see, they split

the bison herd into northern herd and southern herd.

This is how we treat everything. Consider the history of the geographic range

of the American bison -- a very beautiful animal originally found from

Buffalo, New York, all the way to Sierra-Nevada before the 1800s. Huge herds

of untold millions were quickly culled. People back then told about bison

thundering all through the day and all through the night. They called it

"prairie thunder." But that's gone for good, and you're not going

to see or hear it in your lifetime, and that's a loss. When they built the

Trans-continental Railroad, people would buy a ticket and get a gun and load

it with big slugs and shoot bison as they rode across the continent, leaving

their carcasses to rot on the wide open prairie. As you can see, they split

the bison herd into northern herd and southern herd.

Triscuits on the shelves they will wonder "Where did Triscuits come

from?" I fear that we will have to become hunter/gatherers again pretty

soon but Earth cannot support very many hunter/gatherers.

Triscuits on the shelves they will wonder "Where did Triscuits come

from?" I fear that we will have to become hunter/gatherers again pretty

soon but Earth cannot support very many hunter/gatherers.

Carbon dioxide is turning out to be a big thing that could really spell out our

demise sooner maybe than many people think or realize. Big oil and

governments don't want you to know about this. CO2 has risen

steadily to almost double normal levels due to our burning fossil fuels and

cutting down and burning up forests. This has caused

Carbon dioxide is turning out to be a big thing that could really spell out our

demise sooner maybe than many people think or realize. Big oil and

governments don't want you to know about this. CO2 has risen

steadily to almost double normal levels due to our burning fossil fuels and

cutting down and burning up forests. This has caused

I recommend Heinberg's "The Party's Over. Oil, War and the Fate of

Industrial Societies" -- a chemist once told me, "it's like we were

on a luxury liner and we're on the upper floor of the ship and there's a hole

in it and it's sinking, but everybody's having a big party up here, and it's

just a matter of time until we are all underwater." This is Heinberg's

message -- he carefully researched all the facts. It's a doomsday book but

he's an optimist so he has this optimistic end where he lays out what we can

do, as individuals, if one is to live lightly on the land, you know, lessen

your footprint -- drive a Prius instead of an Excursion -- it'll save you

money -- ride a bicycle -- grow your own food. He has all kinds of good

ideas. Unfortunately, even if you do all you can to minimize your own

footprint on Earth, many others won't. Cleaning up the trash along highways

merely makes things seem better and fosters litterbugs.

I recommend Heinberg's "The Party's Over. Oil, War and the Fate of

Industrial Societies" -- a chemist once told me, "it's like we were

on a luxury liner and we're on the upper floor of the ship and there's a hole

in it and it's sinking, but everybody's having a big party up here, and it's

just a matter of time until we are all underwater." This is Heinberg's

message -- he carefully researched all the facts. It's a doomsday book but

he's an optimist so he has this optimistic end where he lays out what we can

do, as individuals, if one is to live lightly on the land, you know, lessen

your footprint -- drive a Prius instead of an Excursion -- it'll save you

money -- ride a bicycle -- grow your own food. He has all kinds of good

ideas. Unfortunately, even if you do all you can to minimize your own

footprint on Earth, many others won't. Cleaning up the trash along highways

merely makes things seem better and fosters litterbugs.